The Autumn Statement: does austerity really work?

In advance of today's Autumn statement from the UK Chancellor, Gerard Gallagher questions the value of using austerity to balance the books.

The autumn statement is due shortly. In these next few days there will be political pundits, bloggers and armchair economists vying to make sense of the economy and the direction in which the Chancellor is planning on taking us. There will be much talk about the debt and deficit and of course the great horror of our age: austerity.

But let’s take a step back first; six years’ worth of steps in fact.

In 2010, the economy was seemingly on the mend following the 2007/2008 financial crash – in part due to coordinated government action on the international scale. Gordon Brown was then Prime Minister and his popularity was under assault. Labour had the helm of the British Economy for almost 13 years and what a mess they made of it. The data was pretty clear; the crash was fuelled in part by excessive Labour spending. They got greedy and left the tap of public finances on for far too long. The solution we were told was austerity. The IMF labelled it “Growth-friendly fiscal consolidation”.

The Sunday Times printed a letter signed by 20 economists urging spending restraint, (although, opposed by 60 the following week), George Osborne was quoting from Reinhart and Rogoff and the thrifty Swabian housewife was the ideal we were advised to emulate. Reckless spending caused this mess and the solution for our ailing economy was a good dose of austerity. Or so we were told. Today, many of the 20 have recanted. The IMF has softened its stance substantially and a spreadsheet error has diluted the strength of Reinhart and Rogoff’s assertions. Despite all of this, many still believe the myth of austerity.

Now let’s focus on one point; government spending. Many arguments against austerity look primarily at the undesirable social outcomes. Few look at underlying economics. Recently, I empirically tested the claims made by austerity proponents and one by one the relationships these proponents expected weren’t present in the data.

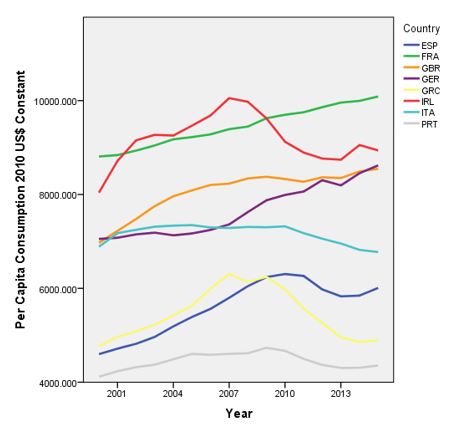

In the following graph I looked at a handful of countries from 2000 to 2014. I controlled for inflation exchange rates (values set at 2010 $ constant) and population size. There may be some country specific variation in population age, but this cannot explain the differences. Italy for example has an older population than Germany, so age-related spending is not largely a factor.

The graph below shows average spending per person, in each country over the period.

We can see in the UK (GBR) spending did indeed increase in the early Labour years. Even so, the U.K. is fairly middle of the pack for an OECD country, especially a rich one. Nowhere in this graph do we see excessive spending – except perhaps Ireland. We see a slight increase in 2007 as the crisis hit, followed by a reduction in late 2009/2010 as austerity measures began to kick in before levelling off and slightly increasing late 2012/2013. This would coincide with the fears over a “double-dip” recession and the apparent easing of austerity measures. What is important to note is that by 2014, Germany was outspending the U.K. despite being the staunchest ally of austerity politics. The relationship we are looking for is between Germany and the U.K.

Economic theory tells us that in times of crisis, governments should spend to stave off the worst – most of this is done via automatic stabilisers such as out of work benefits. In 2007, U.K. spending increased slightly. In contrast Germany exhibits clear evidence of stimulus.

Austerity was based upon flawed economics and driven by political considerations – it was introduced to combat national debt and it hasn’t. Phillip Hammond has the chance to undo his predecessor’s bad decisions.

When he delivers his statement, we will see if he is guided by evidence or more concerned with playing politics.

The featured image in this article has been used thanks to a Creative Commons licence.