Habemus Papam: Comparing the papal visits of 1979 and 2018

In light of Pope Francis' visit to Ireland this weekend, Dr Marie Coleman looks at how the Ireland of today has changed since the last papal visit in 1979.

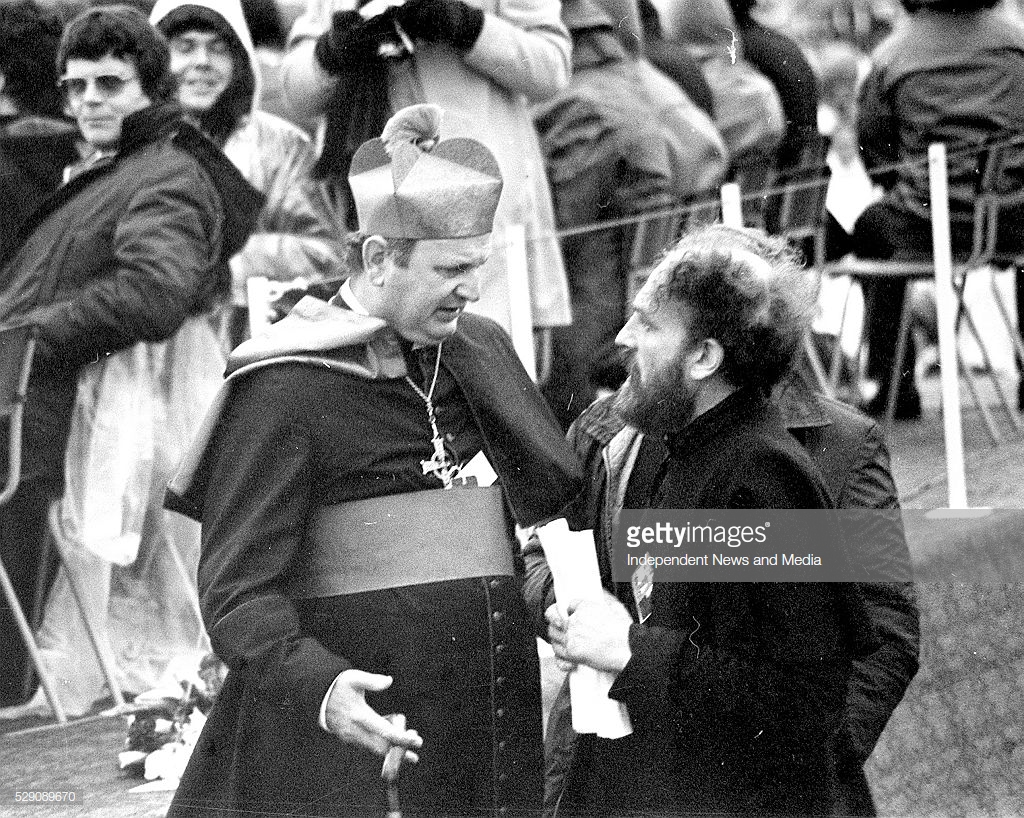

(Image of Bishop Eamon Casey and Fr Michael Cleary at a youth mass in Galway during the papal visit to Ireland in 1979. Image courtesy of Getty Images)

The Ireland that Pope Francis will visit at the end of August is a very different place from the one visited by his predecessor, Pope John Paul II, in September 1979. In the intervening thirty-nine years Ireland swung to the right introducing a constitutional prohibition on abortion (1983) and refusing to remove a similar restriction on divorce (1986), before moving fast in a diametrically opposed direction with referendums legalising divorce (1995), same-sex marriage (2015) and abortion (2018).

The conservative reaction of the 1980s owed much to the encouragement given to right-wing Catholic activists by the 1979 papal visit. The sermons which John Paul preached at masses in Dublin’s Phoenix Park, Galway, and Drogheda all rejected materialism, divorce and abortion, as epitomised by his cautionary note in the Phoenix Park that ‘The most sacred principles, which were the sure guides for the behaviour of individuals and society, are being hollowed out by false pretences concerning freedom, the sacredness of life, the indissolubility of marriage, the true sense of human sexuality, the right attitude towards the material goods that progress has to offer.’

Anti-abortion campaigners had begun organising in Ireland prior to the papal visit, in response to the 1974 Irish Supreme Court decision in the McGee case which held that the constitutional right to privacy extended to marriage and the right to use contraception. Similarities in the legal rationale of the McGee case with the 1973 Roe V. Wade case in the United States led to concerns that the legalisation of abortion would be the natural corollary of the McGee decision. Although abortion was still illegal under British legislation dating from the 1860s, a campaign was started to copper-fasten that prohibition with a constitutional restriction. This resulted in the controversially-worded 1983 eighth amendment, which was repealed earlier this year.

One of the most iconic images from the 1979 papal visit is that of the crowd for the youth mass at Ballybrit racecourse in Galway being entertained in advance of the pope’s (much delayed) arrival by the Bishop of Galway, Eamon Casey, and Father Michael Cleary of Dublin. It would later emerge that both men were fathers in more than the religious sense. At the time of the pope’s visit Casey had a five-year-old son born of a brief relationship with a vulnerable family friend while he was Bishop of Kerry. The revelation of this affair in the Irish Times in May 1992 caused a massive scandal within the Irish Roman Catholic Church leading to Casey’s resignation and effective permanent exile from Ireland. Three years later it emerged that Cleary had fathered two children with his house-keeper.

These scandals were followed by a deluge of revelations about abuse and cover-ups in individual dioceses (Dublin, Cloyne, and Ferns) and in church-run residential institutions including industrial schools and homes for unmarried mothers. A judicial commission investigating matters relating to mother and baby homes is still in progress in the Republic of Ireland. A similar investigation into historical institutional abuse has taken place in Northern Ireland.

These inquiries highlighted the extent to which the Irish state abdicated its responsibility to care for the vulnerable and marginalised in Irish society, relying instead upon the church to make such provision and effectively ignoring what went on behind closed doors. While such residential institutions are no more, and measures for reporting suspected abuse have been introduced, the state’s ongoing reliance upon the church to cater for the social and economic needs of many on the margins of society remains.

Pope Francis will pay a private visit to the Capuchin Day Centre for the Homeless run by Brother Kevin Crowley and a variety of volunteers, including religious, situated in one of Dublin’s poorest regions in the north inner city. This will draw unflattering international attention to the severity of homelessness in Dublin, one of the greatest social problems facing Ireland today. The Irish state’s seeming inability to solve this crisis, and the ongoing need for religious organisations to fill a vacuum that the state appears unwilling or unable to, has strong echoes of the state’s historic delegation of responsibility to deal with social problems to the church.

The catalogue of abuse revelations combined with generational change has resulted in a decline in the number of people in the republic who identify as Roman Catholic; the 2016 census indicated that 78 per cent of the republic’s population were Catholic, in contrast to 93 per cent in the census held in 1981, two years after John Paul’s visit.

In spite of this downward trend, and the evidence from the two recent referendums that a significant majority of Irish Catholics reject many of their church’s moral teachings, in excess of 500,000 people are expected to greet the Pope at three public events to be held in Dublin (the Phoenix Park and Croke Park) and Knock, the site of a reported Marian apparition in 1879. The all-Ireland Football Final has even been put back a week to allow for use of Croke Park by the Pope on Sunday evening. It remains to be seen what type of protests, motivated by the church’s failure to deal adequately with abuse, the Pope will encounter.

Another significant difference between the Ireland of 1979 and today is the situation here in Northern Ireland. The north did not form part of the itinerary for either visit. Suggestions that John Paul might visit Armagh were abandoned in the wake of the assassination of Lord Mountbatten and the Narrow Water ambush, which resulted in the deaths of eighteen British soldiers, on 27 August, a month before the papal visit. The Troubles were central to the Pope’s sermon in Drogheda in which he appealed to ‘all men and women engaged in violence … to turn away from the path of violence and to return to the ways of peace.’

Pope Francis’s visit is unlikely to have the same effect on Irish society as did that of John Paul. Nevertheless, it highlights the ongoing relevance of the church in dealing with social problems such as homelessness. Observers will watch with interest to see if the Pope can address adequately the past failings of the Roman Catholic Church on child abuse. It will also be interesting to see if he refers to the ongoing political impasse in Northern Ireland in any of his public utterances.

The featured image in this article is used under a Creative Commons licence.