Finding a way back to the EU

The Good Friday Agreement contains a mechanism that would allow Northern Ireland to return to the European Union. The EU has confirmed that this will be automatic. Yet this remains a neglected aspect of current constitutional conversations. It is likely that the appetite for this discussion will intensify in the years ahead, linked to Brexit and other factors, says Colin Harvey

It was predicted that Brexit would have a destabilising impact on relationships across these islands. That this insight has turned out to be the correct matters little at this stage. Although this is a debate whose origins rest largely in England, and the anxieties of one political party in particular, the island of Ireland is now at the heart of a Europe-wide conversation.

Few seemed to have listened to the warnings, and the Northern Ireland electorate was never likely to have influenced the outcome (although people did make their view on Brexit clear). The border on the island becomes an external border of the EU after Brexit, with all the symbolism that this carries, combined with the severe practical implications.

Many still appear to be struggling to grasp the EU-specific dimensions of the border question; a matter that will continue to be of profound concern to the Irish Government and the EU.

The collapse of power-sharing government in Northern Ireland in January 2017 underlined the scale of ongoing tension and division, with Brexit forming one part of a complex picture. The decision of the largest unionist party (the DUP) to back Brexit was always going to pitch this in unionist-nationalist terms.

Although there is clear evidence of voting alignment along the lines of national identity, there is also widespread cross-community unease in the region. The DUP, for example, has found itself in conflict with a ‘remain’ majority, and voices from across civic society that are unconvinced by the alleged benefits of Brexit.

The level of disquiet about the prospect of a no-deal outcome in particular resulted in a remarkable mobilisation that has drawn on extensive international and European solidarity and support. The lines of argument, and the parameters of these debates, have been exhaustively discussed and are well known. There is, however, a neglected constitutional discussion that flows from the Good Friday Agreement. That is the possibility of a future vote on Irish reunification as a way back to the EU, and this is the main focus here.

Legitimate constitutional futures

The Good Friday Agreement put in place a sophisticated set of arrangements in an attempt to deal in a comprehensive way with the conflict. It received overwhelming endorsement on the island of Ireland on May 22, 1998.

At the heart of this Agreement is a constitutional compromise designed to nurture peace. The status of Northern Ireland rests on the principle of consent, and the Agreement includes a specific formulation of the right of self-determination. Constitutional aspirations are supposed to be equally legitimate, and relationships based on partnership, equality and mutual respect.

The region has an accepted and agreed exit route from the UK. This is recognised in international law and domestic law in both states, and the Agreement has been lauded widely during the negotiations. Although the emphasis is on the people of the island of Ireland, the triggering mechanism in the UK is tied closely to the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland.

The British government, therefore, has a major say in how this is taken forward. The discretionary nature of this power shades into duty when it appears likely that a majority would vote for a united Ireland. The logic of this is compelling. If status rests only on consent, a time may come when the evidence suggests that the ‘sovereignty arrangements’ are effectively no longer legitimate. That is the imperative underpinning the Agreement and why it is vital that consent is tested.

This focus on a referendum on Irish unity is not to suggest that the principles of the Agreement on parity of esteem, mutual respect and equal treatment fall away, it is simply that Northern Ireland’s continuing membership of the UK requires democratic interrogation.

In fact, the entire process, and what follows, will be framed and guided by the principles of the Agreement. Questions therefore will emerge around when the Secretary of State would commence such a process, how it would be structured, what the question would be and who would be able to vote, for example.

Also, the wisdom of leaving this to the British government looms large at present. In practice it is unlikely that this would proceed without discussion and agreement with the Irish government, particularly as consent must be concurrent; there will be referendums in both parts of the island.

It would make much more sense for this to be preceded by Irish-UK-EU dialogue that uses the existing mechanisms of the Agreement. For example, the British-Irish Intergovernmental Conference would be an ideal forum for the governments to plan a way forward, following wide and deep civic engagement, and dialogue with the political parties.

Although this conversation is steadily being ‘normalised’ (not a week passes in Ireland without a commentator feeling the need to say something about it or someone in Britain musing on the future of the union) it is not one that either government is keen to pursue at present.

What seems remarkable and noteworthy about the conversation in Ireland is that it is so often referred to in managerial terms, and in ways that reflect concerns about constitutional responsibilities and contingency planning. Many of the interventions are focused on preparation rather than immediate calls for a vote.

There is a growing sense, due to a range of factors, that this is something that is coming and it is better to reflect on this way forward in an informed, inclusive and sensible way (learning the right lessons from the Brexit experience in the UK). So, the argument that there should be a forum/convention/assembly established in Ireland to take this forward reflects the complexities of the situation and challenges the unhelpful tendency to do nothing at all.

The new pluralists?

Brexit arguably creates a distinctive proposition on Irish unity. If the UK does leave the EU, the referendum in Northern Ireland also becomes a debate about return. The EU has already provided clarification: the whole territory of a united Ireland would be part of the EU. This opens a new dimension in the context of a society where a majority of people have voted to remain, and where many are profoundly worried about the impact of Brexit.

It would, of course, be a mistake, in a society divided on ethno-national lines, to connect this vote with support for Irish unity. Many self-identified unionists are supportive of staying in the EU, but do not seek a change in constitutional status.

What Brexit does is alter the nature of the future constitutional conversation. One additional and potentially powerful argument those advocating for Irish unity will now have is being part of the EU once again. The persuasiveness of this will depend on the type of Brexit that emerges, and much of this will have to be tested against what happens in practice. For example, if Northern Ireland did secure a special arrangement that essentially conserves many of the benefits of the current position it might change the nature of that debate. Equally, a no-deal Brexit or any form of hard Brexit will simply energise the unity discussion.

What Brexit does is offer space for an Irish unity argument that is distinctly more pluralist and transnational in nature. In this scenario it becomes a way back to a supranational organisation whose foundational objectives chime well with the values underpinning the peace process.

This contrasts with the language and approach that has emerged from the Brexit debate in Britain, where – despite assurances about the centrality of the Good Friday Agreement – there has been an abject and persistent failure to grasp what it means in practice for the region.

Ways forward?

There is an urgent need to normalise the debate around concurrent referendums on the island of Ireland on possible constitutional futures; a debate sometimes reduced to the language of a ‘border poll’. If the constitutional status of Northern Ireland rests on the principle of consent, then it will be tested in the way anticipated in the Good Friday Agreement.

Brexit is bringing an intensified focus on the border, with determined attempts made to protect and conserve the benefits of the peace process.

One consequence is the commendable effort to secure a legally robust way to do precisely that. The debate on the backstop has been instructive. It is a good faith attempt to shield Northern Ireland from the harmful consequences of Brexit, and was shaped through a process of careful negotiation.

Its presentation in many of the London-based debates suggested misunderstanding or wilful misreading. The attempt to establish a bridging conversation to the future relationship was consistently undermined by the self-imposed constraints of the British government. The tragedy was, and remains, that at the heart of this was a sincere attempt to salvage the good will that had gone in to relationship building over the previous two decades.

It is entirely understandable that much of the focus of the EU and Ireland has been on securing a withdrawal agreement, with the objective of achieving as orderly a Brexit as possible. The aim here is to highlight a neglected component of the current constitutional conversations. The Good Friday Agreement contains a mechanism that would allow Northern Ireland to return automatically to the EU. It is likely that interest in this will intensify.

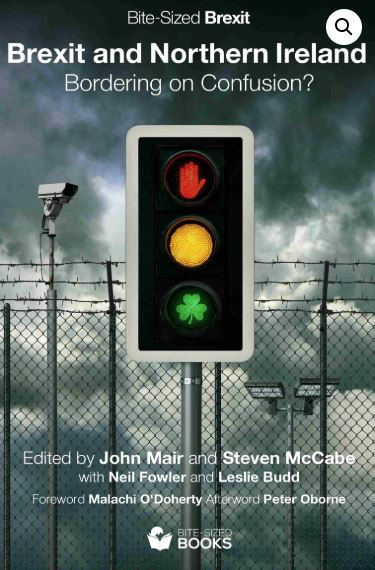

Above text is from a Chapter by Professor Colin Harvey in the Bite-Sized Brexit Series entitled Brexit and Northern Ireland: Bordering on Confusion? Edited by John Mair and Steve McCabe with Neil Fowler and Leslie Budd. Published 25 September 2019. ISBN: 9781694447807