Muslims in Scotland: The Making of Community in a Post-9/11 World

Dr Stefano Bonino from the University of Birmingham looks at the settlement and development of Muslim communities in Scotland and explores what it means to be a Muslim in modern day Scotland.

The construction of Muslim identities in Scotland, within a global climate that has often contested Muslims’ belonging to the Western countries where they live, operates at the intersection of religion, ethnicity and nation. While a shift from ethno-cultural to religious identities is not necessarily a uniquely Scottish experience, the relationship between national and religious identities, mostly among young Muslims, finds a particularly strong resonance in the Scottish context.

In such a context, Islam binds together an ethnically heterogeneous set of people who affiliate globally and locally and respond to the post-9/11 climate through the common destiny and the sense of belonging offered by their religion. This goes hand in hand with strong Scottish identities, which are less ethnically fixed and more inclusionary than English identities, and which allow Muslims to integrate with people of other faiths and cultures under a national banner of civic unity, belief in social justice and a sense of tolerance. Islam – as a religion and a way of life – and Scottish nationalism emerge as the bonds and the bridges that unite diverse Muslim constituencies with one another.

The marriage between nation and religion in defining Scottish Muslims takes a distinctive form in changing notions and practices of community. In contemporary definitions of Muslimness, ethnicity and heritage culture are being partly sidelined by younger generations. Nowadays, being a Muslim is no longer coterminous with being Pakistani or Bangladeshi or Tunisian or Somali. The fact that younger generations are departing from their parents’ and other relatives’ experiences of migration to Scotland is not in itself a major discovery.

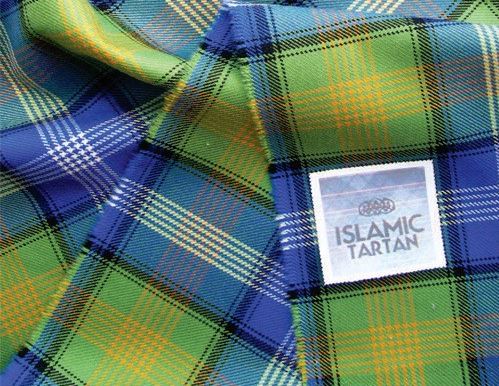

Migrants tend to reproduce their sociocultural patterns in the new setting, in order to preserve their identities and sense of nationhood. Moreover, family subcultures, as instilled by first-generation Muslims, sometimes problematically relate to mainstream society and can aggravate the social exclusion experienced by second- and third-generation Muslims. In this regard, intergenerational changes and transformations are an obvious consequence of the deeply Scottish experiences of Scottish-born Muslims and of some younger migrants. Scottish Muslims’ life perspectives and social practices are dressed up in tartan and play the music of Islam.

Nowadays, being Muslim in Scotland is often coterminous with being religiously and ideologically Muslim and being nationally and civically Scottish. And herein lies the novelty, as this has consequences for the dynamics of that collective aggregate of people of various ages, ethnicities and social classes who affiliate with Islam, live in Scotland and come together to form what is called a ‘Muslim community’. Better still, this should be called a new Muslim community. The new Muslim community equally gravitates around Islam and Scotland in ways that have never happened before. Undoubtedly, the relationship between Islam and Scotland is not free from obstacles: segregationist and anti-Western tendencies among some people within the Muslim community and anti-Muslim sentiments on the part of a minority of Scots are telling examples. Yet, this relationship feeds into powerful narratives of belonging to, and unity with, religion and nation which colour the practices of the community Muslims in Scotland.

The fact that Muslims in Scotland form part of a small, dispersed and relatively well-off community has facilitated social integration. This same community has ostensibly refrained from advancing serious minority claims. In fact, neither faith nor language claims have been strongly pursued in the quest for institutional recognition. Scotland has yet to open the doors to its first Muslim school, while Urdu, the language spoken by many Pakistani Muslims, is nowhere near achieving institutional recognition or the cultural importance that Gaelic possesses.

A lack of serious minority claims, in a context that has not restricted Muslims’ capacity to voice their aspirations for recognition, has played out to the advantage of sociocultural cohesion. Although Urdu and Islamic schools have not entered the institutional landscape, Muslim communities have still managed to make Scotland their home, express allegiance to the country and achieve positions of political power.

Pakistanis, the largest ethnic minority constituency (58.5 per cent) within the Scottish Muslim community, have not only promoted a positive business image to the public and have preferred house ownership and private renting – thus avoiding competition for public services in the 1950s and 1960s – they have also, and very importantly, stayed away from major troubles. The 1988–89 disturbances related to the Rushdie Affair and the 2001 and 2011 England riots were not mirrored by similar violent action in Scotland.

It is true that the small Scottish Muslim community has a limited capacity to mobilise on the streets compared to its English counterpart. It is also true that South Asian gangs, who have populated Glasgow since the 1960s and have mostly fought against other South Asian gangs, have also clashed with the white majority. However, violent tensions between South Asians and white people, such as those in Pollokshields in 2003, have ‘never reached the scale of the riots of Bradford, Burnley or Birmingham [. . . mostly] due to the good relations between the local Asian community leaders and the local white community’.

Both my research and the recently published report ‘Scottish Muslims in Numbers’ suggest that Muslim experiences in Scotland are encouraging, largely due to the Scottish sociocultural context, small settlement numbers, geographical dispersal and the economic conditions of the community. It is true that Scotland should not take all the credit, as it is socially and politically located within a larger multinational State. But it is equally true that despite the perils that it encounters and will continue to encounter, the relationship between Scotland and Islam has the potential to succeed.

This article contains verbatim extracts from the author’s academic monograph Muslims in Scotland: The Making of Community in a Post-9/11 World (Edinburgh University Press, 2016).