Over the next few days, voters in the United States will decide if they want a woman President for the first time. The highest glass ceiling in the world may yet be shattered. Yet a quick scan of political leadership around the globe shows that men over-dominate politics in the 21st century. Women hold less than one quarter (23%) while men occupy over three quarters (77%) of the world’s parliamentary seats today.

Only 53 (19%) women preside over one of the Houses in 193 parliaments worldwide. There are seven women Prime Ministers (including Angela Merkel and Teresa May), 20 elected Heads of State, and two sovereign monarchs (Queen Elizabeth II of UK and Queen Margrethe II of Denmark) in the 193 UN-recognised countries in the world. These figures show the stark male-domination of political leadership today. Indeed, Laura Liswood, founder of the Council for Women World Leaders, captured the challenge of having more women in positions of political leadership with her observation that “There’s no such thing as a glass ceiling for women: just a thick layer of men”.

Yet, there have been obvious – if incremental – improvements in the gender profile of politics. The Nordic countries are now at gender balance with 41% of parliamentary seats held by women, 59% held by men. Other world regions are not as advanced in gender power-sharing, with Latin and South American countries in second place with an average 28% female and 72% male legislators. Some individual countries stand out – in Rwanda the gender balance is reversed, with women holding 51 (64%) and men 39 (36%) seats in the country’s parliament. Bolivia, too, has a majority female parliament (53%), while Cuba’s elected assembly is equally balanced between female and male representatives.

In Europe, the October 29th parliamentary election in Iceland brought in 30 (48%) women and 33 (52%) men, making it the most gender-balanced legislature in the region. It also saw women lead two of the three largest parties in the Althing – Katrin Jacobsdottir of the Left-Green Party and Birgitta Jonsdottir of the Pirates Party. On the other hand, women hold just 89 (20%) seats in the 435-member United States House of Representatives. The gender distribution of seats in the House of Commons is somewhat better, with 191 women (29%) and 459 men (71%) returned at the 2015 general election.

The slow and uneven pace of change prompts us to consider what factors inhibit the achievement of gender equality in political leadership. The supply-side proposition that women ‘lack confidence’ to put themselves forward has been increasingly questioned. Instead, the lack of female role models in political leadership is seen as depressing women’s ambitions to hold office. As Barbara Burrell observed: “Women in public office stand as symbols for other women”. Research shows that women parliamentarians serve as role models to women in society, encouraging their interest and involvement in political life.

Tackling the cultural bias towards males in political leadership has brought about a range of actions. Some encourage the participation of women in political life, such as highlighting role models – as in the Portugese ‘Women can do it!’ project – and candidate mentoring programmes such as that run by the German Helene Weber Kolleg. Others, such as Women for Election in Ireland, focus on building women candidates’ campaign knowledge and representational skills.

Another factor is the demand-side aspect, that of candidate selection. Political parties decide who gets to be on the ballot, and much research has gone into understanding and challenging the deep-rooted bias against selecting women and favouring men as party candidates. While Argentina was the first country in the world to introduce a 30% candidate gender quota law in 1991, France pioneered the compulsory 50% candidate gender quota in 1999.

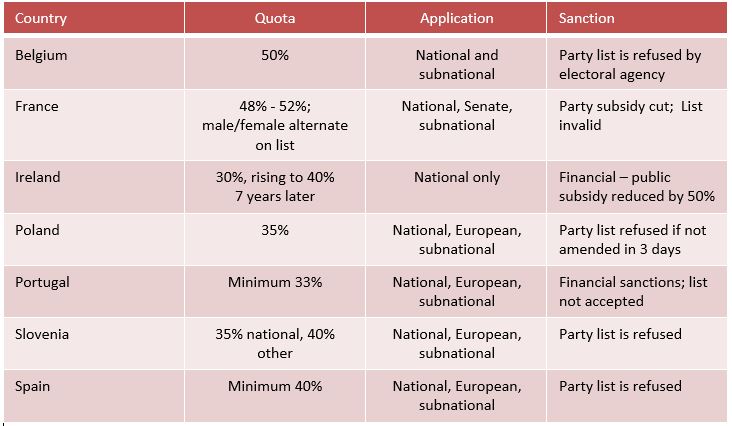

Since then, quota laws providing for a minimum threshold of female and male candidates have been adopted in 85 countries and territories around the world. Seven EU Member states have adopted this type of legislation:

The expectation underpinning the adoption of candidate quota laws is that the rebalancing of the pool of those eligible and available to serve at the next level of leadership will lead to greater gender equality in political leadership. While a candidate gender quota is a controversial means of improving the gender balance in political leadership, the evidence is that this is a measure that works. In Argentina, women’s share of parliamentary seats rose from 5% in 1991 to 36% in 2015. The adoption of a quota law in Slovenia led to women’s share of legislative seats increasing from 13% in 2001 to 37% in 2014.

A greater gender balance in parliamentary seats can lead to a more equitable gender distribution of government positions. The Slovenian government is gender equal, with 8 female and 8 male ministers along with a male Prime Minister. The 30 ministerial posts in the Rwandan government are shared among 11 (37%) women and 19 (63%) men. In contrast, Argentina’s executive branch consists of 3 women (18%) and 19 men (82%), despite the higher representation of women in parliament.

A more recent trend is for incoming Prime Ministers to appoint gender-balanced, and sometimes gender equal, cabinets without waiting for an increase of women in parliament. The cabinet of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is gender equal, with 15 women and 15 men, even though women hold 88 (26%) seats in the Canadian House of Commons.

Bringing gender balance to political leadership, then, is an ongoing project. While individual women’s personal achievements are important, the real power of these achievements rests in the symbolic message sent to the public. This message is that women can, do, and should share political leadership with men.

If Hillary Clinton is elected president of the United States, not only will she have achieved the pinnacle of power for herself, she will also have achieved it on behalf of women. She will join Theresa May, Angela Merkel, Aung San Suu Kyi, and Ellen Johnson Sirleaf in the rare but growing group of women who have reached the highest political office. The ‘thick layer of men’ will have taken a significant step closer to becoming a layer of equals.

The featured image in this article has been used thanks to a Creative Commons licence.