In Part 1, John Moriarty discussed the evolution of policies on alcohol use in Australia. He showed how the idea of harm minimisation, which has guided the response to illicit drugs since the 1980s, came to inform official attitudes to harmful alcohol use.

When teenagers weigh up the decision to drink, are they really thinking about adding or subtracting years to the end of their life, or that of their liver? Probably not, so while important information for young people to hear, explaining potential health impacts can’t be the only way we discuss alcohol use with young people. This becomes particularly apparent when you dig into the consequences of different levels of alcohol use during adolescence.

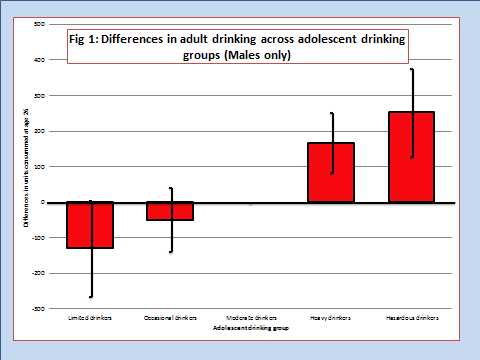

The above diagram shows the relationship between drinking during adolescence with drinking habits at age 26, as measured in the British Cohort Study. Each group is defined by their pattern of drinking at age 16. The height of each bar represents how many additional units of alcohol an individual was predicted to have consumed at age 26, based on the group they were a member of at age 16.

The main significant difference is between heavy or hazardous drinkers and moderate drinkers, with heavy drinkers in adolescence more likely to become a heavy sessional drinker in early adulthood. One reading of these results is that if enough people could be diverted from heavy drinking into moderate drinking during adolescence, then in the medium term fewer adults would drink at hazardous levels and the disease burden on the population from alcohol use would be a lot lower. So perhaps the best approach would be to teach and model moderate drinking to younger people.

This is easier said than done. Parents and educators may be anxious that by pitching the message of moderate drinking to a young person, that they are tacitly approving alcohol use at an age when none would be preferable. What is required is a nuanced message along the lines delivered in sex education: it’s healthier if you wait, but if you choose not to, here’s how to make sure you’re being as safe as possible.

However, thinking back to the Australian experience, perhaps the goal of harm minimisation isn’t best achieved by advocating moderate drinking. In Part 1 of this blog, we highlighted the unexpected adverse effects John Toumbourou described of informing parents that supervised drinking in small doses might help young people to develop healthy drinking habits. He points out that individuals respond differently to health messages. Some are responsive and take advice on board, while others don’t, and often those that don’t are the same people who use behaviour such as substance use to shape their identity and persona. So, if many adolescents are drinking to a moderate degree, how do you stand out? By drinking to excess, perhaps. Therefore, Professor Toumbourou suggests that by advising no alcohol use during adolescence, those who rebel will only need to drink moderately in order to achieve their objective.

This idea of playing to the gallery and drinking to maintain social status brings us back to another idea introduced in Part 1. This is the idea that a person’s substance use harms others as much as it harms him or her.

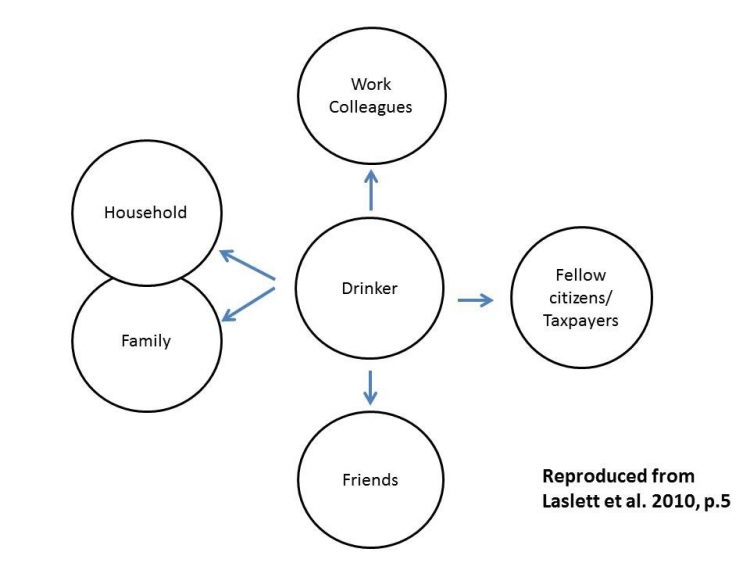

In the above diagram, blue arrows point to persons likely to be harmed from an individual’s alcohol use. That harm is particularly experienced by those closest to the individual and is most acute where use is heavy or hazardous. Harms in this scheme can range from abuse suffered while a family member is intoxicated, to accidents caused by persons under the influence, to the cost to the taxpayer of removing debris from streets near pubs and clubs. But one additional, more complex avenue for harm is social influence: the decision to binge drink may contribute to the decision of a friend or loved one to do the same and to risk their own health, which may indeed be greater for them.

Perhaps, then, rather than focussing on distant threats to one’s own health, awareness campaigns could appeal to young people’s sense of social responsibility and attachment to those around them. By raising young people’s awareness of the various harms their drinking could bring about for people that they care about, including the idea that may influence a friend drink when they’re not ready yet, parents and educators could open up a more positive dialogue with young people.

So what do we do? We conclude that any strategy for engaging young people needs to:

- be sensitive to the age of the young people being targeted, which particular risks go with moderate or heavy drinking at that age, and what is the likely norm around drinking in their social circles;

- be sensitive also to the fact that people respond differently to health messages and that other types of messages will be more effective;

- to grow awareness of the ways in which other people, especially close friends and families, can be harmed to others, including via social influence.

Shortly after John’s visit to Melbourne, he and Andy gave a joint presentation and policy brief reflecting on Northern Ireland’s policies around alcohol use among adolescents as part of the Knowledge Exchange Seminar Series at the Northern Ireland Assembly in Stormont. They were subsequently invited to discuss their recommendations with the Children, Young People & Families Advisory Group of the then Department for Health, Social Services and Public Safety.

The featured image in this article has been used thanks to a Creative Commons licence.