How did the new Irish state created in 1922 establish structures and capacity to undertake the political, economic and societal aspirations of both its political class and wider population? The Decade of Centenaries programme has provided fruitful and necessary reappraisal of the post-1912 period of state formation. Much has been written about the politics and personalities of the period, and key moments that led to the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty. Less attention has perhaps been given to the administrative model and culture that would determine the ‘type’ of polity the Irish Free State was to be, and how it would be organised to raise revenues, regulate and deliver public services. As we approach a centenary since the formal transfer of administrative authority from Dublin Castle to the Provisional Government of the Irish Free State on 16th Jan 1922, it provides a moment to survey a century of bureaucratic development.

That the model of public administration the new state would adopt retained the defining characteristics of the British Whitehall model – generalist, politically impartial, career-based and intensely hierarchical – is perhaps not surprising given political energies were elsewhere focused as Civil War loomed. It was nonetheless a missed opportunity to think about establishing a more decentralised form of power distribution or a new type of professional civil service. There was however little appetite to consider European models of public administration, with their heavier emphasis on statutory public authority, legal training for civil servants and extensive codification. Nor did contemporary US ideas around progressivism and the use of science in government catch hold (though the US ‘city manager’ system heavily shaped Irish local government reforms in the 1930s).

Instead, the essential features of Whitehall, which had undergone a period of intense reorganisation and cost-saving rationalisation after WWI (including in Ireland), were to inform the Irish Free State’s model of government. Without doubt, there is a lot to be applauded and the relative stability of the state after the Civil War owes much to the continuity of practice in this system. Not that it was a seamless transition – as Maguire (2009) identifies huge numbers of public servants shifted positions between London, Dublin and Belfast as new constitutional realities took form. However, in keeping with a key characteristic of the bureaucratic form of organisation – resistance to rapid change – the structures of government remained broadly familiar. Under the seminal 1924 Ministers and Secretaries Act, power would reside with Ministers who would be deemed responsible for the activities of their Departments in their entirety. This Act still determines much about the operation and accountability of the Irish public service today.

An initial attempt to cull the number of organisations in the inherited administrative system did not last long. Almost 60 organisations survived the period of formal transition between 1922 and 1924 including many familiar ones such as Ordnance Survey Ireland (1824), the Office of Public Works (1831), the Irish Prison Service (1854) and several ‘royal chartered’ bodies. Other long forgotten organisations have had their functions assumed by successor agencies, including the Quit Rent Office (1641-1943), the Inspectorate of Factories (1901-56) and the Commissioners of Charitable Donations and Bequests for Ireland (1845-2014). And within a year of establishment, as well as the new Ministries and Offices of state, new organisations such as the Irish Film Censor’s Office (1923-2008) and National Education Commissioners (1923-35) were created.

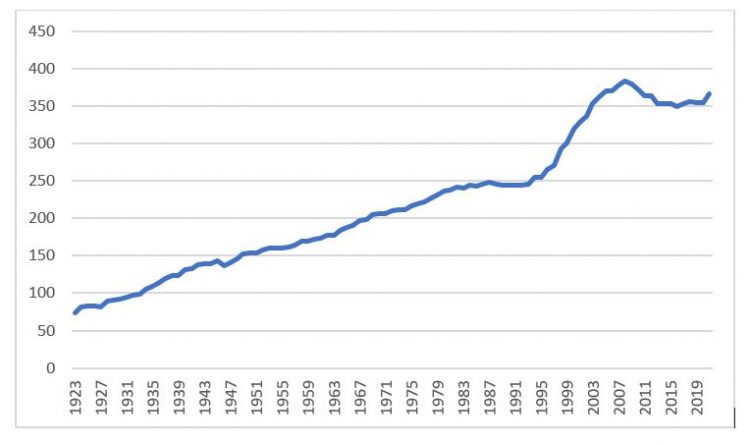

All told, in the century since the handover in Dublin castle, almost 900 national-level public organisations have played a role in delivering an ever-growing range of public services and state obligations. As the Figure (below) identifies, this gradual accumulation of organisations continued unabated (with the exception of a brief period of state contraction during WWII) until the 1990s. Many of these entities now barely appear as historical footnotes, but in their time manifested the policy concerns and objectives of government, such as the Commission on Emigration and Other Population Problems (1948-54), Corás Beostoic agus Feola Teoranta (1969-79) and the Combat Poverty Agency (1986-2009).

Figure 1: Number of public organisations per year 1922-2022

Source: Irish State Administration Database (as of January 2022)

Source: Irish State Administration Database (as of January 2022)

The Celtic Tiger period of economic expansion facilitated a rapid and sustained period of administrative expansion that was also arrested by the 2008 crash. The post-2008 period was one in which for the first time a concerted effort to reduce the number of organisations was made. But as the economy recovered, new agencies emerged such as the Legal Services Regulatory Authority (2016), Office of the Planning Regulator (2019) and the Approved Housing Bodies Regulatory Authority (2021)

Over 350 national-level public organisations today perform a wide variety of functions, but there remain enduring questions about their management and coordination. An attempt to establish a more formalised model of state agency management arose with the seminal Devlin report on public service published in the late 1960s, and again following the creation of the Department of Public Expenditure and Reform in 2011. But the model of centralised government focused on powerful ministerial departments, to which a host of agencies with varying levels of autonomy and accountability continues to characterise Irish public administration.

This inherited model is today under considerable pressure. In 1922 there were 11 Departments with discrete policy briefs. Today, the number of Departments (18) is as many as there has ever been, and with parties in coalition governments seeking to introduce ever more policy initiatives, the responsibilities of Departments have increased enormously. These multiple and diverse responsibilities are reflected in lengthy titles, such as the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media, or the Department for Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth.

The Republic of Ireland has proved itself to be well capable of experimenting with new forms of democratic decision-making over the last decade, with forums such as the Citizens’ Assembly receiving international acclaim. We are now experiencing major technological changes within government, and far-reaching changes in the way citizens engage with the system of public administration. As the state begins its second century, it may be time to look afresh at the art of the state in Ireland.

The featured image has been used courtesy of a Creative Commons license.