GCSEs have recently undergone major changes in England, Northern Ireland and Wales. Until 2013 they were jointly controlled by the qualifications regulators in these jurisdictions. However, disagreements regarding the ways that GCSEs should be assessed led to the end of three country regulation in 2013. There are now significant differences between how the qualifications are assessed in England, Northern Ireland and Wales.

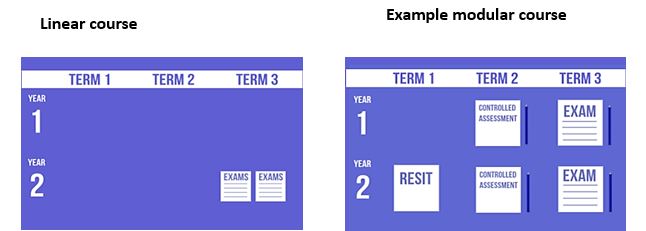

England’s approach has been to use linear courses for all subjects: this means that students are assessed by examinations only and wholly at the end of their course. In contrast, in Northern Ireland and Wales, controlled assessment and modular courses are still used for some subjects. For these subjects, the GCSE is split into different units and students can be assessed either at the end of the module or wholly at the end of the course (the linear option).

Despite these changes, there is very little research that asks students about their views and experiences of different assessment structures, and they have been left out of the debate on the most recent reforms in the UK.

We would suggest that the omission of young people from the debate is problematic given the UK’s commitment to enabling young people to participate in decisions that affect them, under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. The omission is also surprising given the dominance that assessments, like GCSEs, have in the educational experiences of children and the use of such assessments as ‘currency’ exchanged for places on further and higher education courses; assessment at 16 and 18 is at its most intense and its most critical in terms of impact on children’s lives.

Recent research conducted at Queen’s University Belfast used focus groups and a questionnaire survey with current GCSE students (aged 15-16) in Northern Ireland and Wales to find out what young people thought about these issues.

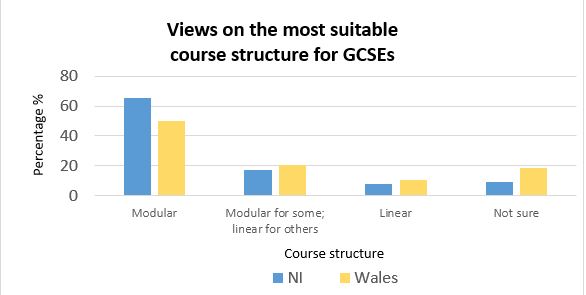

As shown in Figure 1 below, students in both regions were supportive of modular courses, with most students opting either for modular courses to be used across the board, or for a mixture of modular and linear courses.

In their responses, students were able to reflect in sophisticated ways on how course structure affected learning. They indicated that they found it easier to learn when the course was divided into modules, and the focus of a module enabled them to develop ‘a strong understanding’ of a topic (Male student, NI). Modular assessments throughout the course also gave them a better idea of how they were progressing and ‘more chance to correct mistakes’ (Male student, Wales).

In contrast, the minority who preferred linear courses tended to do so because they found constant assessment stressful, and because they felt they performed better when they had completed the entire course, as this enabled them to foster connections between different elements of the subject.

However, regardless of which course structure they preferred themselves, the majority of students indicated that more flexibility was better for students overall, because ‘everyone learns differently’ (Female student, Wales). They suggested that the difference between students means that a variety of options should be available to all and felt that their current situation, in which some students are assessed using modular courses, and others using linear ones, was unfair. Research has shown that these different types of assessment components can be differentially beneficial to one group of students over another – the classic studies were carried out in relation to gender where boys were more likely to prefer examination only courses and girls more likely to prefer courses that had coursework elements.

Similarly, students wanted more choice over which tiers they were entered for at GCSE. For most subjects that are tiered at GCSE level, there are two tiers of exam paper – the higher tier (providing access to grades A*-D/E), and the foundation tier (providing access to grades C-G).

Many of the student in our study called for more involvement in decisions about which tiers they would take – noting that the curriculum was restricted on the foundation paper and that it was thus difficult to move up to a higher tier.

As this research has shown, there is already a considerable amount of variation in the ways that not only young people are assessed, but also in the way that schools implement GCSEs to maximise their school’s outcomes. Thus, we are arguing that there is space for students to be involved in discussions with regulators, awarding bodies and within schools about assessment. Moreover, if we want to design assessments that get the best performance out of pupils then we need to involve students in decisions about qualifications at all levels.