Setting the Context for the 2017 Assembly Elections

In light of the imminent elections, Dr Christopher Raymond looks at the changing size of the Northern Ireland Assembly and anticipates the potential impact of this reduction on parties’ seat shares.

Most of the focus of debate regarding the 2017 Assembly election has been on the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) scandal and on the consequences of this scandal for the DUP. While this focus is understandable, one also needs to consider the impact of another major issue: the changing size of the Assembly. Because the number of MLAs being returned to the Assembly has shrunk from 108 to 90, smaller parties will have a harder time competing this year. This means that the parties scrutinising the DUP’s actions may have a difficult time dislodging the party from government.

The Impact of Altering the Size of the Assembly

Previous literature notes that the number of seats returned to legislatures – both in terms of the number of seats returned in each constituency and the number returned overall – helps determine the number of viable parties. In a comprehensive (yet accessible) study summarising his many contributions to the field, Rein Taagepera demonstrates how the number of viable parties can be predicted fairly well by knowing two pieces of information: the number of seats returned to a legislature and the average number of seats returned in each constituency. When either of these numbers is increased, this model predicts the number of parties winning seats and the overall fragmentation of seats across parties will increase. By the same token, this model also predicts that reducing either number will make it harder for smaller parties to win seats while seat shares become more concentrated in the largest party.

In the upcoming Assembly election, both the number of seats returned per constituency and the number of seats returned overall have been reduced: 5 seats per constituency (down from 6 in 2016), and 90 in total (down from 108). As a result, Taagepera’s model predicts that smaller parties will have a tougher time winning seats this year, while the largest party in 2017 will benefit from these parties being shut out from the Assembly. These points have not escaped the attention of some in the media, who have rightly posed questions to smaller parties about their electoral viability. Though smaller parties may benefit from the RHI scandal and outperform the expectations of this model, the fact remains that smaller parties certainly face a tougher environment in which to get elected than they did in 2016 now that the number of seats has been reduced.

An Insulated DUP?

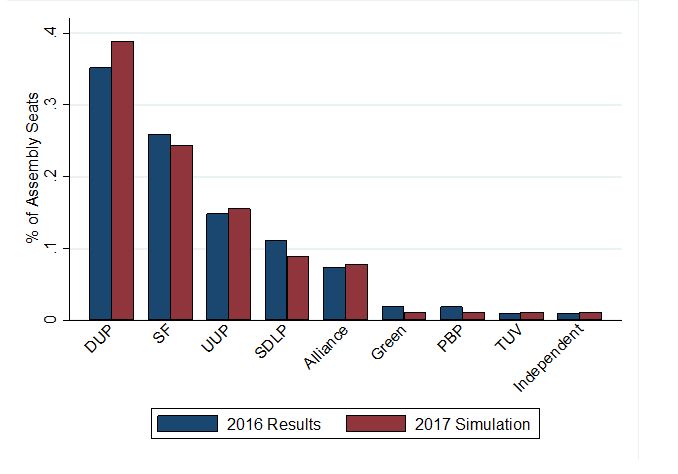

This model’s predictions could easily be borne out in next month’s election. In particular, one interesting possibility is that the reduction in the number of seats may actually benefit the DUP and insulate the party from the effects of the RHI scandal and the scrutiny the party faces from smaller parties. As evidence of this possibility, I examined the distribution of seats after each round of seat allocations in each constituency in 2016 for each party. To simulate the outcome of the 2017 election, I simply deleted the sixth seat in each constituency from that party’s seat total. The result gives us an idea of how next month’s election might turn out if the assumptions made above are valid.

In 2016, the DUP won 11 of their 38 seats in the first round of seat allocations (either outright on first preferences or after transfers began to be allocated). 30 of their 38 seats were secured after the fourth round of seat allocations, while only three seats were allocated as the sixth seat in the constituency. This suggests that the DUP start from a healthy position to weather out the RHI scandal: eliminating the sixth seat in every constituency would actually increase the party’s standing at Stormont, giving it 35 of 90 seats (39% in the new Assembly compared to 35% after the 2016 election).

The data also show that smaller parties would generally be hurt by the reduction in the number of seats. Though the UUP and Alliance would ultimately have a larger share of the overall number of seats despite losing 2 and 1 seats, respectively, both Sinn Féin and the SDLP would see their seat shares decline further. The Greens and People Before Profit would each lose a seat, while the TUV would only hold onto its one seat (though this seat would constitute a slightly higher share of the total in the Assembly). This would leave us in much the same position as now, with the DUP and Sinn Féin forced to contemplate forming a government yet again.

Of course, all this assumes the DUP are not poised to be punished by voters at the polls. That certainly remains within the realm of possibility; if so, the DUP could potentially be unseated from power. However, recent polling suggests the assumptions made above are not far off. Combined with the historical record of elections to Stormont, this suggests we can expect the 2017 election to be yet another head count. Even if the DUP’s first-preference vote share dropped by the amount suggested in recent polling, the fact that Sinn Féin’s standing remains at least as high as in 2016 means that we can expect DUP campaigners to appeal to unionist voters reminding them that transfers to the DUP in subsequent rounds of counting might be necessary to prevent O’Neill from becoming first minister.

So in conclusion…

The discussion above is not meant to serve as a prediction, but rather as a starting point for setting expectations for the 2017 election. Because previous research suggests that shrinking assembly sizes hurt small parties, we can expect that the DUP will likely benefit from the reduction in the number of seats. While campaigns can seriously change the trajectory of an election, it will take a campaign that produces much bigger changes to the parties’ anticipated vote shares to impact the makeup of the next Assembly in a meaningful way.