The impact of de-peering on internet provision

Dr Subhadip Chakrabarti looks at the networking agreements that connect internet networks and highlights the impact of de-peering on these agreements.

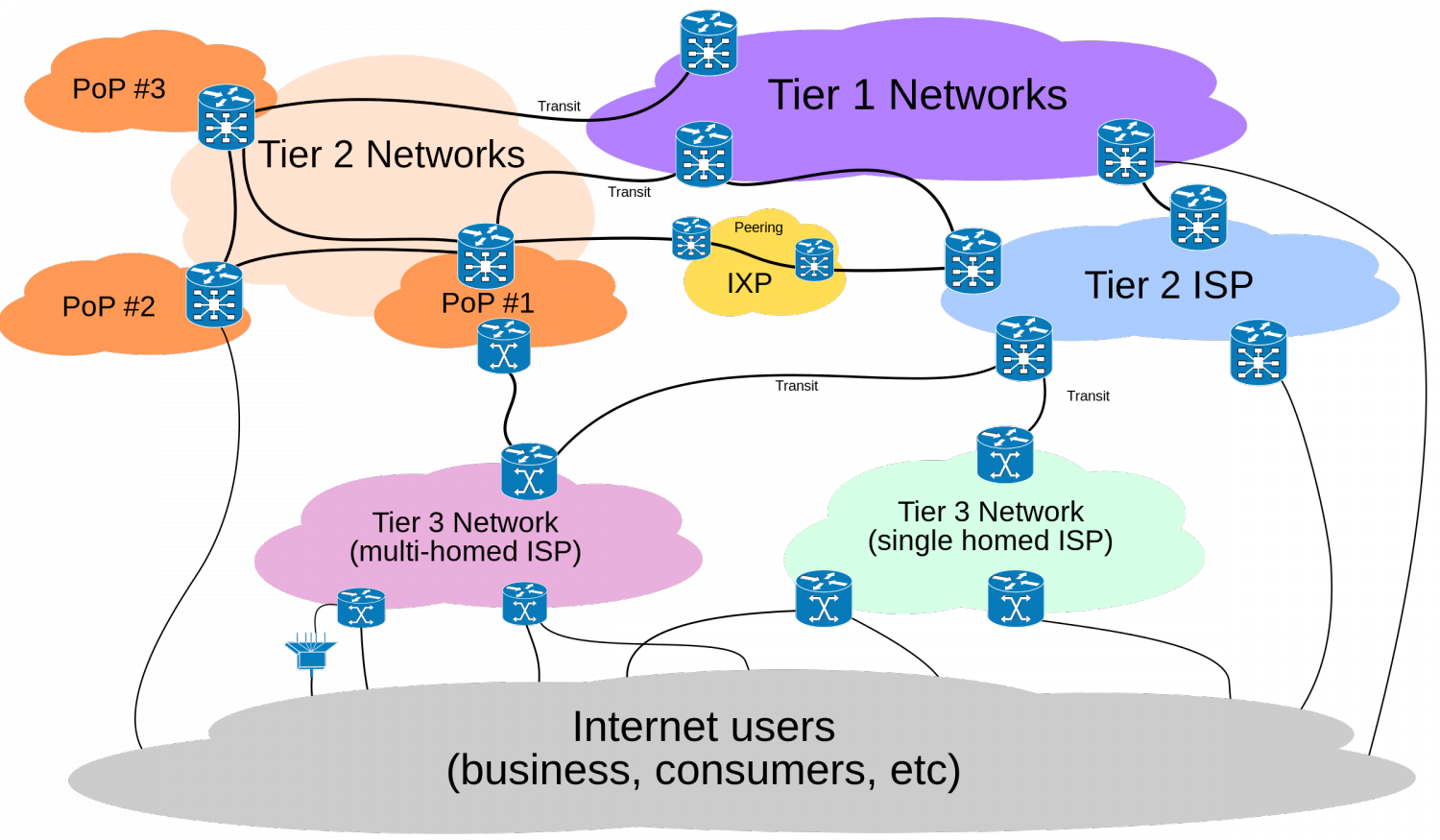

The Internet is a super-network, or a network of networks. Each individual network is called an autonomous system or AS, consisting of computers connected via fibre-optic or copper lines and routers to direct Internet traffic.

Each firm has its own network. The end-users of the Internet are consumers and websites. End-users generally want to have access to all other possible end-users, regardless of the network they are attached to. To provide such universal connectivity to their users, the firms must interconnect with each other and share their network infrastructure.

Two main forms of interconnection emerged following privatisation of the Network Access Points – peering where firms carry each other’s traffic without any payments and transit where the downstream firm pays the upstream firm a certain settlement payment for carrying its traffic.

Transit agreements typically include a two-part tariff: a flat monthly fee and a volume based variable fee. Transit agreements also include a service level agreement (SLA) under which the transit provider maintains the network and carries out repairs and resolves network problems. Peering is a legacy of the public sector origins of the Internet. After the privatisation of the NSFNET in 1995, the commercial backbone providers would peer at the Network Access Points (NAPs). These NAPs were the forerunners of the more modern Internet Exchange Points (IXPs). Later on, when these NAPs became congested, they would peer privately, and in such peering only mutual traffic was allowed and third party traffic was not allowed.

Currently, peering at IXPs is known as public peering while peering at private interconnection points is known as private peering. The Internet has a loosely hierarchical structure. At the top are Tier 1 networks, most of whom are in the U.S. These are transit free networks and only peer with one another. Tier 2 networks both peer and purchase transit. Tier 3 networks mostly purchase transit, and operate in the retail market. They provide internet access to individuals and also host websites.

Tier 2 and Tier 3 networks have a choice between single-homing and multi-homing. Single-homing means that the Internet Service Provide (ISP) in question has connectivity to the Internet only through one Tier 1 provider. This is risky because if the provider loses connectivity due to a peering dispute for example, the ISP in question will lose all connectivity. So, a safe strategy is multi-homing; connectivity to the Internet through multiple Tier 1 providers, but the latter is also a lot more costly and out of the reach of small providers.

De-peering

De-peering refers to the termination of peering agreements. This can happen at all levels. However, it is more common in situations where at least one of the parties in the peering dispute is a Tier 2 or a Tier 3 provider. There are two main reasons for de-peering: traffic asymmetry and the market power of large Tier 1 networks.

Let’s look at traffic asymmetry first. Consider two providers peering with one another. One provider primarily hosts websites, and the other primarily provides internet access to customers who want to browse the web. Under hot potato routing, most of the traffic is carried by the second network. So, it makes sense for the second provider to start charging for carriage of traffic instead of offering free access. Peering works well when traffic flows are reasonably even in both directions. With asymmetric traffic flows, transit becomes the preferred alternative for at least one of the providers.

Second, transit brings in valuable revenues while peering does not. With the maturing of the Internet, Tier 1 providers have become significantly larger and gained market power. So, they have been increasingly in a position to demand transit from smaller providers with few adverse consequences. With the Tier 1 network dominated by few large players, transit has increasingly replaced peering for the smaller service providers.

Table 1 below provides a partial list of de-peerings from 2000 to 2008.

Table 1

| Year | Parties Involved |

| 2000 | PSINet-Exodus |

| 2001 | Cable & Wireless-PSINet |

| 2002 | AOL-Cogent |

| 2003 | France Telecom-Proxad |

| 2005 | France Telecom-Proxad |

| 2005 | Level 3-Cogent |

| 2008 | Cogent-TeliaSonera |

| 2008 | Sprint Nextel-Cogent |

De-peering has not, until now, posed a threat to connectivity in the Internet. In spite of many de-peerings, the Internet remains healthy and is growing. What de-peering does is impose a temporary inconvenience on some users, and is usually resolved in some fashion. For instance, the dispute between Level 3 (a Tier 1 provider) and Cogent (a Tier 2 provider) in 2005 took three days to resolve.

Part of the reason for this is that peering disputes have seldom involved two Tier 1 providers, and most disputes take place between larger and smaller providers. Regulatory agencies such as the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) have been reluctant to intervene in any way or impose any regulation on the service providers. The only regulation that the FCC imposes on providers is broadly referred to as “net neutrality”, i.e. providers should not favour one kind of traffic over another, no “fast lanes” for extra payment are allowed.

In contrast to other industries, the Internet is one of the most deregulated industries. Providers operate in near total secrecy and are free to set tariffs as they choose. The prevailing philosophy is that the Internet has thrived without regulation this far and any attempt to regulate the Internet would stifle competition and might do more harm than good.

At present, there is very little appetite to enact legislation to prevent de-peerings.

The feature image in this article has been used thanks to a Creative Commons licence.