Northern Ireland: the challenge of public opinion

Professors John Coakley and John Garry share the results from a major new survey into how the Northern Ireland electorate voted at the recent UK referendum on EU membership.

The interplay between the public stance adopted by political leaders and the positions preferred by their supporters is an important issue in all democracies. We can now explore this relationship in greater depth in Northern Ireland in the context of the Brexit vote, using a major new survey supported by the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council, conducted in the weeks immediately before and after the referendum and with a sample of over 4,000.

Surveys of this kind are often marked by a tendency to under-report minority positions, especially if these are subjected to widespread public criticism. There is evidence that some ‘shy Brexiters’ who misreported their views may have been present in the survey. Although in the referendum, 56% voted to remain in the EU, in the survey those saying they had voted or would vote ‘remain’ came to 60%. In fact, if the views of all respondents are taken into account, those preferring the ‘remain’ position would come to 62% (this includes a significant group who had not voted and said they probably would not, breaking 70-30% in favour of ‘remain’).

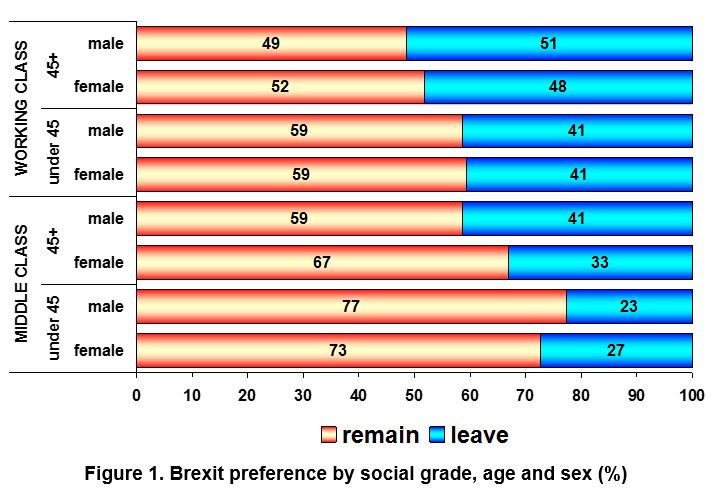

The social characteristics that were important in Britain in explaining how people voted were important in Northern Ireland too. Support for Brexit was stronger among the working class, among older people, and among males. Figure 1 below shows evidence of this trend in Northern Ireland. Support for the ‘leave’ position was strongest among working class men aged 45 or more (the top bar of the graph). We might expect it to be weakest in the bottom bar (middle class women aged under 45), but women were pipped at this particular post by men. The broad trend from the top to the bottom of the graph is nevertheless clear.

A more fundamental line of division separated Northern Ireland from Great Britain. When we look at religious background, its role in explaining different attitudes towards Brexit is obvious: 85% of Catholics supported ‘remain’, but only 41% of Protestants did so (with 59% supporting Brexit). There were similar differences in other, overlapping, areas of division: 88% of those describing themselves as Irish supported ‘remain’, but only 38% of those describing themselves as British took this position (with ‘Northern Irish’ identifiers in between, at 64%). Among those describing themselves as ‘nationalist’, similarly, 89% supported ‘remain’, a position adopted only by 35% who described themselves as ‘unionist’ (with those opting for ‘neither’ coming in the middle, at 70%).

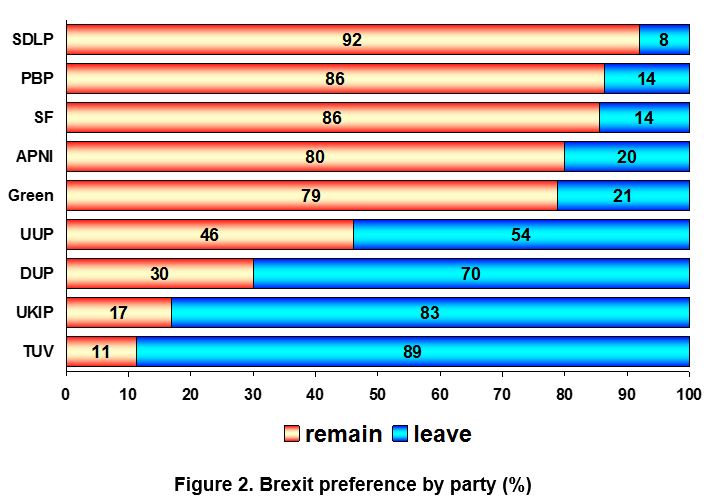

These divisions are vividly illustrated in Figure 2, which looks at attitudes towards Brexit among supporters of all parties which were represented in the survey by at least 50 respondents. The four lower bars represent the unionist parties, the two smallest of which (UKIP and TUV) were, unsurprisingly, the strongest supporters of Brexit. But majorities of DUP and Ulster Unionist voters also supported Brexit, notwithstanding the more pro-European stance of the latter. On the nationalist side, supporters of the two big parties, Sinn Féin and the SDLP, were solidly behind the ‘remain’ position, as were those in the centre (supporters of Alliance, the Greens, and People Before Profit).

Since community background is so important in explaining other aspects of political behaviour in Northern Ireland, it is not altogether surprising that it looms so large in respect of the Brexit issue too. It is nevertheless puzzling. There are no particular reasons for expecting Protestants to fare better than Catholics if the UK leaves the EU; the main implications lie in the areas of economy, society and demography. The bonds that currently tie London to Brussels are not highly visible in Northern Ireland, and it is not clear that whatever political gains Brexit might bring to London will pay dividends in Northern Ireland.

On the contrary, Brexit has re-opened the question of the Irish border and has the potential to undermine the finely balanced settlement that has brought peace to Northern Ireland over the past two decades. The data in the survey discussed here, however, show just how divided public opinion in Northern Ireland is on Brexit, and political leaders have to take account of this.

The future of all-Ireland discussions may well depend on the manner in which public opinion in Northern Ireland shifts as the full implications of Brexit become clearer.

For further discussion, see John Garry, “The EU referendum vote in Northern Ireland: implications for our understanding of citizens’ political views and behaviour”, Knowledge Exchange Seminar Series paper, Northern Ireland Assembly, 2016.

(Note: There may be slight variances in the tables reported in the paper above and the figures presented in this note due to slightly different computational methods and approaches to classification).

The featured image has been used courtesy of a Creative Commons licence.