How Can and Should the European Union respond to COVID-19 beyond short-termism….?

In this special long read article, Professor Dagmar Schiek looks at the EU's response to date to the Covid crisis and asks what more should the European Union be doing?

Introduction

While a pandemic reminiscent of the plaque and the 1918 Spanish influenza is raging globally, the European Union (EU) does not seem to win the propaganda war on the most effective and generous response. Trump Tower represents the “muscular response by a strong man”, with him seizing health products ordered by others without paying while also closing borders to protect US employment. China tries to portray itself as the global Samaritan, even though some of the equipment donated or delivered against cash globally seems faulty. The EU, as in any crisis in recent history (as Patrick Bijsman reminds us), finds itself at the centre of speculation whether it will disappear this time, as surely this crisis has the potential to doom the project (which the relevant journalist never liked anyway).

The EU is not a knight in shining armour – but a problem solver

The EU’s first raison d’être, as specified in Article 1 TEU, is for Member States to achieve their common objectives through pooling their sovereignty. The overarching objective here is creating an ever-closer union among the peoples of Europe, with the citizens at the centre. This means that the EU in principle complements national responses, and does not have the aspiration to solve all the problems itself. Thus, the EU cannot be the muscular strong leader (aka a knight in shining armour), but will rather be the competent actor pooling capabilities of all the states and citizens. That makes it so much more difficult to win the propaganda war with the likes of Trump, at least not in the perception of those who need to see a strong individual as leader. It may, however, successfully combat the health crisis immediately emanating from the coronavirus, and develop a suitable medium-term strategy, combining bottom-up and top-down problem-solving in intelligent ways.

The pandemic challenges – far beyond public health

A global pandemic, mainly spreading through droplets emitted by infected humans, is not only beyond local or national resolution, but also requires fundamental reorientations. Of course, it challenges health care systems – the weakest will crack first. Treating symptoms and finding a cure and/or a vaccine may appear the first challenge, and decision makers have wavered between cooperation and competition in meeting this challenge. However, the impact of the pandemic goes far beyond health and health care systems. For those who do not want people to die, it questions the viability of global, national and regional human movement as well as familiar forms of human exchange. The reliance on global interaction through supply chains is reconsidered, as well as employing precarious migrant workers picking crops and caring for people in richer countries where the high-waged national population does not deliver these services. Where public services cannot or will not deliver on the WHO recommendation of testing widely and tracing contacts, or are unable to treat and eventually cure those developing symptoms, decision-makers feel they have to choose between lockdown and wide-spread deaths. In densely populated areas, being confined to one’s home may result in the virus spreading among the poor living in close quarters, while protecting more privileged persons from the same fate.

Even partial lockdown and mere social distancing have dire economic and social consequences. Consumer demand for some items weakens, whole sectors are closed down, international trade wilts, unemployment rises and economic activity contracts. All this has dimensions last seen in the late 1920s. A Friday in 1929 led to devaluation of currencies, soaring unemployment. Inadequate responses by the fledgling European welfare states are generally viewed as one of the main reasons for the rise of far-right populism of the 1930s. The EEC was one of the responses to its deadly consequences. Today’s lockdowns also threaten progress made since then in the field of widely accessible (higher) education, while closures of schools and universities exclude children and young people not availing of adequate tech-equipment from continuing their education. These same closures return to the private home the physical aspects of caring for children, endangering the continued engagement of carers (overwhelmingly female) in gainful work.

Lockdown, control of movement, requirements to constantly monitor one’s health and make the results publicly available also impact on protection of privacy and liberties, potentially ultimately endangering democracy in Western societies – a theme for a separate treatment.

Lockdown, slowing-down public life and social distancing measures have other, not altogether negative consequences. In areas where the internet works well, and technology is highly developed, the pandemic has led to a surge in remote working, seemingly pushing a fundamental change in working styles. Where employers develop sustainable working from home schemes, models such as an alternating four-day week for cohorts of workers may continue to be applied, reducing consumption of time and energy for commuting permanently. That reduction of movement has immensurable positive effects on the environment: we have wild-life re-claiming parts of the world which were closed to them for a long time, and climate change is being partially addressed. The challenge here is to maintain positive side-effects of combating the pandemic in the long term.

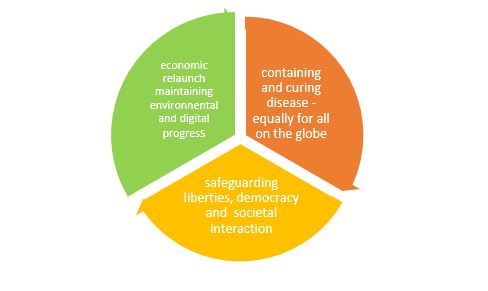

Beyond the truism that a global pandemic requires a response beyond national borders (some call for a global plan), there are three mutually reinforcing challenges.

Framing the EU’s Response

The EU’s response to these challenge must be determined by safeguarding and promoting its specific characteristics which distinguish European integration from any other regional project globally, and from any state. Its crisis response must safeguard three basic characteristics:

(1) The EU is a Union of states, respecting the diverse strengths of its Member States and empowering them through the pooling of sovereignty.

(2) The EU’s unique socio-economic model uses economic integration to achieve non-economic aims such as social and environmental justice and territorial cohesion, achieving a comparatively high level of equality globally.

(3) The EU is a Community based on law (not war or unilateral rule of economic powerhouses) and values including human rights protection. This long read will only look into how to meet the first and second challenge, leaving the third one to a potential continuation.

a) A Response of a Union of Member States

Next to hindering a white knight role, the need to respond as a Union of Member States requires respecting the competence regime of the EU Treaties.

1) Immediate Health (care) crisis

While the EU’s competences in harmonising Member States’ health care systems are limited, it has extensive competences in coordinating policies improving public health, the complementarity of national health care system, promoting research in the causes, transmission and prevention of major health scourges, as well as promoting early warning of and combating serious cross-border threats to health.

EU legislation may incentivise the combat of those health scourges, as well as measures for monitoring and warning (Article 168 TFEU). Conceiving of COVID 19 as merely a health (care) crisis, bloggers have elaborated on what the EU does or should do better. So, we all know about:

- EU funding of CORONA research

- EU pooling procurement of medical equipment and PPE

- EU initiatives to exchanging medical staff

- Member States’ offering treatment capacity across borders

We have learned that coordination of national COVID-19 strategies could be better and that the EU has so far failed to require EUROSTAT to provide up-to-date statistics on infection rates.

2)Beyond heath care crisis activism

Since COVID-19 infections will rage in Europe until early 2021, it is time to look beyond the initial attempts to mitigate the health (care) crisis. The medium- and long-term response should combine regulatory with macro-economic measures (i.e. financial assistance and/or loans), potentially refocusing funds and policies. So far, there is little attention to the degree to which the uneven spread of COVID-19 through the Union will result in a distortion of EU funding and policy focus. While it is not easy to compare the degree of being affected cross-country, the number of infections and fatalities per million citizens is a useful indicator. By that criterion, summarised in this graph, the most affected Member States are Belgium (3986 infections and 612 fatalities per million citizen), Spain (4847 and 469), Italy (3269 and 440), France (3474 and 350) and Ireland (39009 and 220), while the least affected Member States are Latvia (430 and 6), Bulgaria (187 and 8), Croatia (469 and 13), Poland (307 and 14) and the Czech Republic (689 and 20). Those Member States most affected in numbers are relatively wealthy, while those least affected comprise one of the poorest (Bulgaria). While the debate rages between Western Member States, there is a risk that “Corona-measures” disregard the needs of Eastern Member States still requiring better general infrastructure to become comparably competitive with longer-established Member States.

For example, the first EU measure adopted consisted of relaxing state aid rules. This only helps Member States with sufficient resources to provide state aid, while potentially distorting the EU wide economy with repercussions in those less affected Member States mentioned above. This instrument does not take such effects into account. While some authors have already demanded to not disturb market processes, this might not go far enough. It would seem more appropriate to require those Member States able to afford state aid to take compensation measure in favour of competing sectors in those Member States less able to afford it. Alternatively, an EU-wide support programme instead of national state aid might afford greater equity.

b) Defending the European socio-economic model

1) Europe as the continent of relative equality

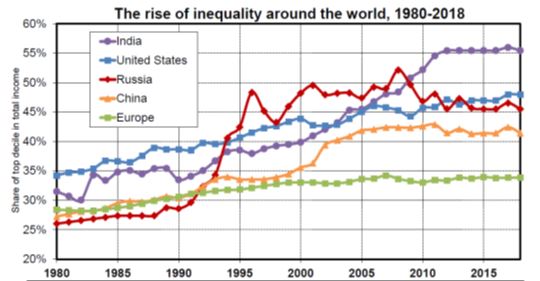

Notwithstanding legitimate critique of the EU’s policies promoting austerity after 2009, the European Union states still maintain significantly higher levels of equality than other regional blocs.

Interpretation. The share of the top decile (the 10% highest incomes) in total national income ranged between 26% and 34% in 1980 in the different parts of the world and from 34% and 56% in 2018. Inequality increased everywhere, but the size of the increase varies greatly from country to country, at all levels of development. For example, it was greater in the United States than in Europe (enlarged EU, 540 million inhabitants), and greater in India than in China. Sources and series: see www.piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology (figure 0.3). Slide by Thomas Pickety.

2) EU competences supporting the European Social Model in the Corona crisis

Mainly, the EU competences to support its Member States in maintaining “welfare state arrangements” (i.e. legislation ensuring that wealth is distributed more evenly among their population than elsewhere) are of a regulatory nature: the EU can harmonise elements of employment, consumer and anti-discrimination legislation (Articles 19, 153 -157, 169 TFEU), create preconditions for free movement (Articles 46, 50, 59 TFEU) and coordinate national policies such as combating poverty and modernising social protection systems (also Article 153 TFEU). These regulatory competences have not been used to full effect in the Corona-crisis, a shortcoming identified through a critique of “SURE” and listing omissions in defending free movement below.

Next to all these regulatory competences, the EU’s ability to provide funding for Member States to overcome this particular crisis are less pronounced, but they do exist. Regular EU funding mechanisms comprise the European Social Fund (Articles 162-164 TFEU), the European Regional Development Fund (Article 176, 178 TFEU) and the European Cohesion Fund (Article 177 TFEU). In 2002 the EU created the EU Solidarity Fund in order to support Central European Countries suffering from disastrous floods, based on what is today Articles 175 and 352 TFEU. The initial Regulation 2012/2002/EC was amended on 30 March 2020 to enable support for Member States and accession candidate countries in response to a public health crisis. These funds are direct support, not loans, though they are limited to €1 million per state, and must not exceed 25% of the actual cost (Article 4 a paragraph 2). They can cover rapid assistance to the population in a major public health emergency, preventing and reactive protection of the population from the risk of being affected, monitoring and/or control of the spread of disease, as well as combating and mitigating the impact of severe risks to public health. (Article 3 paragraph 2 letter e). The EU also has the power to create additional solidarity instruments in cases of a crisis (Article 122 TFEU), which was complemented by the European Stability Mechanism as an extra-Treaty instrument in the global economic crisis of 2009.

3) An exemplary assessment: SURE between funding instrument and regulatory response

So far, the debate around the EU’s adequate response has focused on injecting funds into Member States, either directly or through loans. German angst of funding “reckless Italians” contra-factually disregarded Germany’s disproportionate gain from the Eurozone. Even if “conditionality” is justified in normal times, its deployment for addressing expenditure required to boost health-care systems and provide other Corona-responses is no longer demanded by the European Council. The long-term strategy to address the fall-out of a serious global economic crisis while maintaining the ecological gains of the overall slowdown can only succeed if the dogma that the economy needs relentless growth is abandoned. Alas, conditionality is based on a growth model, as is its Keynesian critique – more questions for another blog. In the meantime, using Article 122 (2) TFEU as a basis for loans, instead of financial support, is to be questioned, while the extent of the emergency package surely needs expansion. All this disregards the relevance of regulatory responses through harmonisation. A short critical appreciation of the widely praised SURE programme shall illustrate this.

The draft regulation establishing an instrument for temporary support to mitigate unemployment risks in an emergency (SURE) is meant to provide financial assistance to Member States experiencing or being threatened with economic disturbance for financing “of short term work or similar measures aimed to protect employees and self-employed and thus reduce the incidence of unemployment and loss of income” (Article 1), provided that additional expenditure was caused by the COVID-19 outbreak and occurred after 1 February 2020 (Article 2). The regulation goes on to establish the procedure to access the financial support, which comes in the form of loans. There is no indication which measures are comprised by “short-term work or similar measures”.

There is to date no EU level harmonisation in relation to unemployment benefits, not even recommendations, and this also applies to instruments such as “short-time work”. This term is probably meant to refer to the option of an employer to reduce working time for a limited period, including the option of reducing working time to zero. Funded short-time work might be taken to refer to legislation providing for employers to receive public funding to continue paying the wages to employees on “short-time”. The regulation does not distinguish between both, and neither does it make any funding contingent on employers being under an obligation to retain the workers after reopening their business (or returning it to its former operation) when the restrictions imposed are lifted.

Member States are free on whether they require employers to continue paying (reduced) wages and social security contributions, which are then reimbursed by the state, or whether they use short-time work as an alternative or prelude to unemployment. Member States are free to include self-employed or precarious workers, or exclude them from short term payments. There is no mechanism which prevents Member States from changing the rules for short-time work in their COVID-19 legislation in order to diminish employee rights to representation, as has happened already in Poland. Member States could even create legislation awarding employers support to comply with short-time work, without giving employees any right to short-time work. All this means that EU funding based on SURE could be abused to form some additional state aid, depriving the instrument of its intended positive macroeconomic effects.

Devising specifications on the minimum requirements short-term work under SURE should comply with is beyond any blog. However, specifications are necessary, if the EU payments should reach those suffering from a lack of remunerated work due to COVID. For many Member States short-time work is a new phenomenon. This would have called for outlining the basic conditions which national legislation (or collective agreements) would have to comply with in order to justify receiving financial support by the EU. First, the notion of short-time work could have been specified as a temporary reduction of working time (possibly to zero hours) in response to the COVID 19 restrictions for continuing business. An obligation to reinstate the employee upon lifting of restrictions should be added, as well as a clause that employees should be consulted through their representatives (often trade unions). Additional options for covering self-employed workers, as well as limitations to exclude precarious workers in part time, on fixed term contracts or on flexible working time contracts, could be added. This would be an essential supplement of SURE, and thus covered by the original legislative competence.

This suggested combination of SURE as a funding instrument with harmonisation would be a really intelligent solution in three respects:

(1) The Member States’ contribution to the SURE funding instrument would ensure that burdens arising from short-time work which avoids unemployment are shared in solidarity between Member States;

(2) Providing an income to those on short-time (furloughed in UK terminology) maintains purchase power in all Member States, which stabilised the economy in a time of crisis and;

(3) If accompanied by harmonisation, the payments provided are conditional on staying in line with minimum standards, which avoids free-riding while respecting the autonomy of Member States’ social security systems.

4) using the advantages of the crisis: effective guidance on remote working

Even the COVID 19 cloud has a silver lining in that increased remote working has positive effects on the environment. The crisis thus presents the unique chance for the EU Commission to promote the advantages of the Digital Single Market for the world of work. However, that opportunity remains largely unused, if employers all over the EU are allowed to institute remote working without a proper concept, and a relevant plan. The EU Commission’s tasks include issuing guidance in situations such as this. How should EU employment directives be safeguarded? Does the working time directive require employers to ask their employees to log in and out of their work-related computers? Should employers provide extra equipment, and could funding for such equipment be included in the EU contingency measures? How can the rights of on-call workers (including gig-workers), recently promoted through a special directive, be safeguarded? Where is the EU Commission guidance on how frontier workers work from home, which tax system can offer relief for extra investment for home office, and whether Member States really can prevent EU workers from taking up work?

The experiences in Member States with the extreme digitalisation of the world of work could be utilised to draft future guidance to maintain the momentum in order to reduce commuting and traffic, making the world of work “greener” without dumping all the responsibility on those least equipped to deliver. Without addressing the conditions of digitalisation, the changes are likely to either be reversed, or worse, will be retained at the cost of health and safety at the domestic kitchen table.

Conclusion

The EU is far from powerless in addressing the COVID-19 crisis in a sensible way, but it has used these powers selectively. It is to be hoped that the relative inertia evaporates and the vacuum for EU level activity is filled by more imaginative instruments than generating financial injections.

The featured image has been used courtesy of Getty Images and a Creative Commons license.