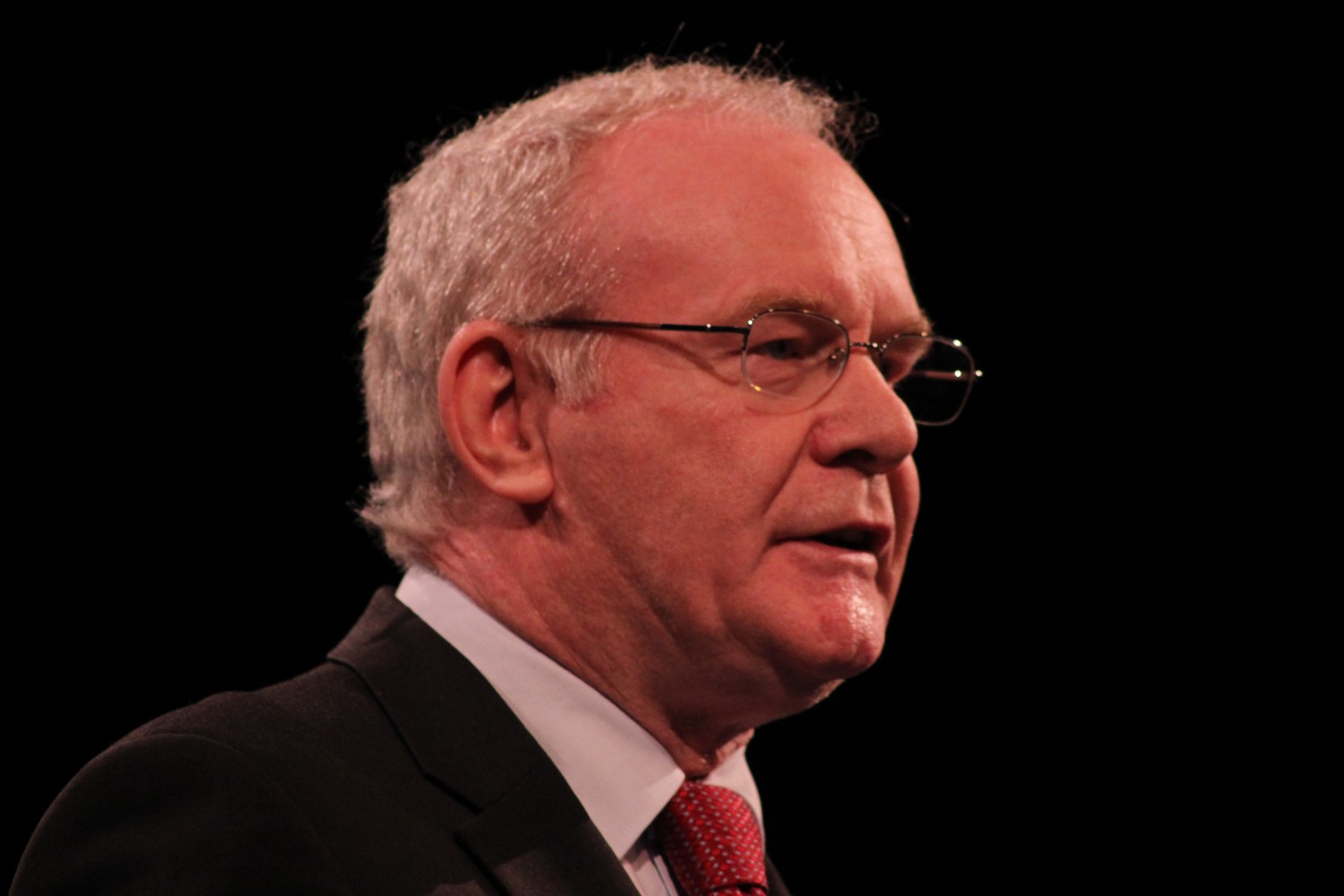

Martin McGuinness – Reimagining Reconciliation for the Future

Dr Gladys Ganiel reflects on a recent event hosted by Queen's University where Deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness reflected on his own personal journey of peace and reconciliation.

Deputy First Minister Martin McGuinness responded to a panel of sixth form pupils in a recent event hosted by the Senator George J Mitchell Institute for Global Peace, Security and Justice at Queen’s University Belfast. The Minister first spoke on ‘Reimaging Reconciliation for the Future’ after which six pupils from Methodist College and St Mary’s CBS shared their reflections on his remarks. Pupils from several other Belfast and Bangor schools were also in the audience.

In his opening speech, the Minister spoke of the peace process as a ‘shining beacon’ internationally, and asserted that we are now in ‘the next phase of the peace process – the reconciliation phase.’ He also linked reconciliation to the 1916 commemorations, saying that they provide republicans with two opportunities: 1) to engage with unionist narratives and understandings of events in 1916, and 2) to promote mutual respect and parity of esteem between the two traditions. He also said:

‘The presence of republicans at Remembrance events is a sign of respect [to unionists]. We need to match our words of reconciliation [by attending] key commemorative events of the unionist community.’

Mr McGuinness spoke extensively about travelling around the world to consult on peace processes, contrasting his experience in Sri Lanka (where he did not detect a desire for peace) to Colombia, where he said that the parties were ready. He added that when he visited Colombia, the people he interacted with already knew about the behind-the-scenes mediation work of Brendan Duddy, and had even nicknamed the FARC back channel negotiator ‘Brendan.’

Mr McGuinness concluded his initial remarks by saying that if we want reconciliation, ‘people have to want to be reconciled. I have a strong desire to be reconciled with people from the unionist community.’

The Deputy First Minister largely avoided reflecting on the difficulties of reconciliation, though he admitted that republicans have been on ‘an emotional and psychological roller coaster’ to arrive at a place where they could talk about reconciliation. He added that there were ‘those in republicanism who tell me I try too hard … [by participating] in initiatives without reciprocation. But it’s the right thing to do.’

Students’ Response

But the pupils didn’t let McGuinness off the hook. One student from Methodist College challenged the Deputy First Minister for presenting the 1916 Easter Rising and Proclamation in such a positive light, saying that he had difficulties with those who used violence to achieve their aims without a political mandate. ‘How can we celebrate 1916 … when dissident republicans use the same rhetoric to justify their actions today?’ He also took issue with the claim that our peace process took place when people had a desire for peace. ‘Throughout the Troubles the people of Northern Ireland wanted peace – what changed was the paramilitaries caught up with the people.’

Three other students from Methodist College emphasized that young people had a more ‘socially liberal’ agenda than most of the politicians on the hill, noting that they were deeply disappointed at the failure of marriage equality. ‘I was devastated when it didn’t happen,’ one pupil said, ‘but I feel more inspired to make it happen.’ Another said: ‘We want gay marriage – but democracy fails us on that issue.’

One student from St Mary’s and another from Methodist College bemoaned the tribal nature of Northern Ireland politics, wondering if and when we could get political parties that transcended the two traditions. ‘I am sick of looking to the past. There is no one to vote for,’ lamented one pupil.

All of the students said that tribal politics had turned some of their peers off from politics. Indeed, during the question and answer period, another schoolgirl remarked from the floor that she ‘wanted politics as a career but none of the Northern Ireland parties represent me.’

At the same time, one of the St Mary’s pupils remarked that Martin McGuinness had inspired him, and it was up to the pupils themselves to inspire their peers – to communicate to them that politics matters.

In his response to the pupils’ reflections, Mr McGuinness observed that ‘this confirms for me that young people are miles ahead of the politicians.’ But he dismissed the idea of post-conflict parties that transcend communal divisions, saying ‘that’s not going to happen’ and arguing that a better course of action is ‘cultivating the ability to work together.’

The Minister was more convincing when he spoke about reconciliation in some of his personal experiences, which he gave in response to queries during questions and answers. By way of example he said he ‘had the unique experience of being reconciled with the Rev Ian Paisley’ when they shared the Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister. He said that when Ian Paisley left office, as a gift he asked Seamus Heaney to hand-write a copy of the poem ‘Hope and History,’ which he framed and presented to Mr Paisley as a token of their friendship. He also presented him with a framed copy of a poem he had written himself.

He spoke further about shaking hands with Queen Elizabeth and the symbolic importance of this, praising the Queen for the way she conducted herself on her state visit to the Republic of Ireland.

Prof John Brewer, who was one of the ‘keynote listeners’ at the ‘Let them Speak’ event for sixth formers at the 4 Corners Festival, was the main organizer of the event. It is the first in a series of events at Queen’s where politicians will respond to young people.

Prof Brewer encouraged those tweeting about the event to use the hashtag #mybillni. This is providing a Twitter forum for young people to share what legislation they would introduce to Stormont, if they could.

Article first appeared on Slugger O’Toole Blog.

The featured image in this article has been used thanks to a Creative Commons licence.