Northern Ireland’s New Domestic Abuse Statutory Aggravator Provisions

Dr Ronagh McQuigg looks at the Domestic Abuse and Civil Proceedings Act (Northern Ireland) 2021, particularly the Domestic Abuse Aggravator Provisions.

The provisions of the Domestic Abuse and Civil Proceedings Act (Northern Ireland) 2021 came into operation on 21 February 2022. The most well known impact of this Act is that it created a new domestic abuse offence for Northern Ireland which effectively criminalised coercive and controlling behaviour. However, it is perhaps less widely known that the Act also contains statutory aggravator provisions, whereby a charge relating to any offence other than the new domestic abuse offence, may be regarded as ‘aggravated’ by reason of involving domestic abuse, thereby resulting in an increased sentence if a conviction ensues.

The Domestic Abuse and Civil Proceedings Act (Northern Ireland) 2021

Under section 1 of the Domestic Abuse and Civil Proceedings Act (Northern Ireland) 2021, it is a criminal offence to engage in a course of behaviour which is abusive of another person where the parties are personally connected to each other; a reasonable person would consider the course of behaviour to be likely to cause physical or psychological harm; and the perpetrator intends the course of behaviour to cause such harm, or is reckless as to whether such harm is caused.

According to section 5(2), the parties are ‘personally connected’ if they are, or have been, married to each other or civil partners of each other; they are living together, or have lived together, as if spouses of each other; they are, or have been, otherwise in an intimate personal relationship with each other; or they are members of the same family. Under section 14, a person who commits the domestic abuse offence is liable, on summary conviction, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 12 months or a fine (or both) or, on conviction on indictment, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 14 years or a fine (or both). The enactment of this new domestic abuse offence is certainly a very welcome development, as it has the effect of criminalising coercive and controlling behaviour, thereby bringing Northern Ireland into line with the other jurisdictions within the UK and Ireland in this respect.

However, the Act did more than simply create a new domestic abuse offence. Under sections 15-16 of the legislation, any other offence may be aggravated by reason of involving domestic abuse if three conditions are met. These conditions are:

- Firstly, that a reasonable person would consider the commission of the offence by A to be likely to cause another person (B) to suffer physical or psychological harm;

- Secondly, that A intends the commission of the offence to cause physical or psychological harm to B, or is reckless as to whether the commission of the offence causes such harm; and

- Thirdly, that A and B are personally connected.

As with the domestic abuse offence, according to section 18 the parties are regarded as being ‘personally connected’ if they are, or have been, married to each other or civil partners of each other; they are living together, or have lived together, as if spouses of each other; they are, or have been, otherwise in an intimate personal relationship with each other; or they are members of the same family which encompasses B being A’s parent, grandparent, child, grandchild, sister or brother. Interestingly, under section 16(3) an offence can be aggravated whether or not the offence was actually committed against B.

As noted in the Explanatory and Financial Memorandum to the legislation, the domestic abuse aggravator could be attached if, for example, the accused committed criminal damage against a friend of their partner with the intention of thereby causing psychological harm to their partner. An offence can also be aggravated whether or not the commission of that offence actually caused B to suffer harm. According to section 15(4)(c), if the charge and the aggravation by reason of involving domestic abuse are proved, the court must in determining the appropriate sentence, treat the fact that the offence is so aggravated as a factor that increases the seriousness of the offence.

In addition, section 23 of the 2021 Act makes complainants eligible for special measures when giving evidence in cases involving not only the domestic abuse offence itself, but also offences to which the domestic abuse aggravator is attached. These special measures may include screening the complainant from the accused; giving evidence by means of a live link; giving evidence in private; or video recording the complainant’s evidence in chief, cross-examination or re-examination. Also, section 24 establishes that no person charged with the domestic abuse offence or an offence to which the aggravator is attached may cross-examine the complainant in person.

The Importance of the Domestic Abuse Aggravator Provisions

The domestic abuse aggravator provisions constitute a very valuable part of Northern Ireland’s new legislation, and have the potential to apply to a wide range of offences. The Statutory Guidance issued by the Department of Justice in February 2022 suggests that the most common types of offences to which the aggravator could be attached include criminal damage, assault, threats to damage property and threats to kill. For example, if someone deliberately caused criminal damage to their partner’s car, the domestic abuse aggravator could be attached to the charge of criminal damage. Historically, the fact that a crime was committed in a domestic context was frequently viewed as a factor which made it less serious. For example, an assault committed between strangers would often have been treated more seriously than an assault by one partner against another. The value of the principle now being encapsulated in legislation that domestic abuse should be seen as an aggravating factor, as opposed to a mitigation, should not therefore be underestimated.

In England and Wales, there is no statutory domestic abuse aggravator, although the Sentencing Council has issued guidelines stating that offending behaviour is more serious in a domestic context due to the violation of trust and security that is involved. Nevertheless it is arguably meritorious that Northern Ireland has chosen to legislate for a domestic abuse aggravator, as this clearly conveys to victims, perpetrators and the public more broadly that domestic abuse is a serious matter which will not be tolerated by the criminal justice system. During the passage of the legislation through the Northern Ireland Assembly, the Committee for Justice reported that the evidence which it had received showed widespread support for this provision.

Northern Ireland’s statutory domestic abuse aggravator is not however the first of its kind to be implemented within the UK and Ireland. In Scotland, section 1 of the Abusive Behaviour and Sexual Harm (Scotland) Act 2016 came into force in April 2017. Under this provision, an offence is aggravated if in committing the offence, the perpetrator intends to cause their partner or ex-partner to suffer physical or psychological harm; or in the case of an offence committed against the partner or ex-partner, the perpetrator is reckless as to whether such harm is caused.

If the offence and the aggravation are proved, the court must take the aggravation into account when determining the appropriate sentence. In the Republic of Ireland, section 40 of the Domestic Violence Act 2018 provides that where a court is determining the sentence in relation to certain offences, the fact that the offence was committed by the perpetrator against their spouse or civil partner or against someone with whom they were in an intimate relationship, should be treated as an aggravating factor. However, although the aggravator provisions in Scotland and the Republic of Ireland came into effect substantially earlier than those in Northern Ireland, it is notable that Northern Ireland’s provisions are significantly broader than those of the other jurisdictions. The provisions in Scotland and the Republic of Ireland relate only to partners and ex-partners, whereas Northern Ireland’s aggravator provisions encompass a wider range of family relationships. Also, for an offence to be aggravated in the Republic of Ireland, the offence must be committed against a partner or ex-partner; whereas in Northern Ireland an offence can be aggravated even if it was not actually committed against the person to whom the perpetrator is personally connected.

In addition, the aggravator provision in the Republic of Ireland can be used only in relation to particular offences such as a range of offences against the person, rape, sexual assault and aggravated sexual assault. By contrast, the aggravator provisions in Northern Ireland can be used as regards any offence, apart from the new domestic abuse offence itself. The fact that Northern Ireland has chosen to adopt the most expansive approach is arguably advantageous, as this allows the aggravator provisions to be used in the widest range of cases.

Looking to the Future

The new domestic abuse offence and the new domestic abuse aggravator provisions together constitute a milestone in the response of the criminal justice system in Northern Ireland to domestic abuse. Far from a domestic abuse context being seen as lessening the seriousness of an offence, it is now very firmly established that not only is domestic abuse a criminal offence in itself, but it is also to be viewed as increasing the seriousness of other offences in terms of sentencing. Given that the Domestic Abuse and Civil Proceedings Act (Northern Ireland) 2021 has only come into operation very recently, it will be some time before a substantial body of jurisprudence is built up in relation to either the domestic abuse offence or the domestic abuse aggravator provisions. Nevertheless, both have the potential to contribute significantly to increased protection for victims of domestic abuse in Northern Ireland.

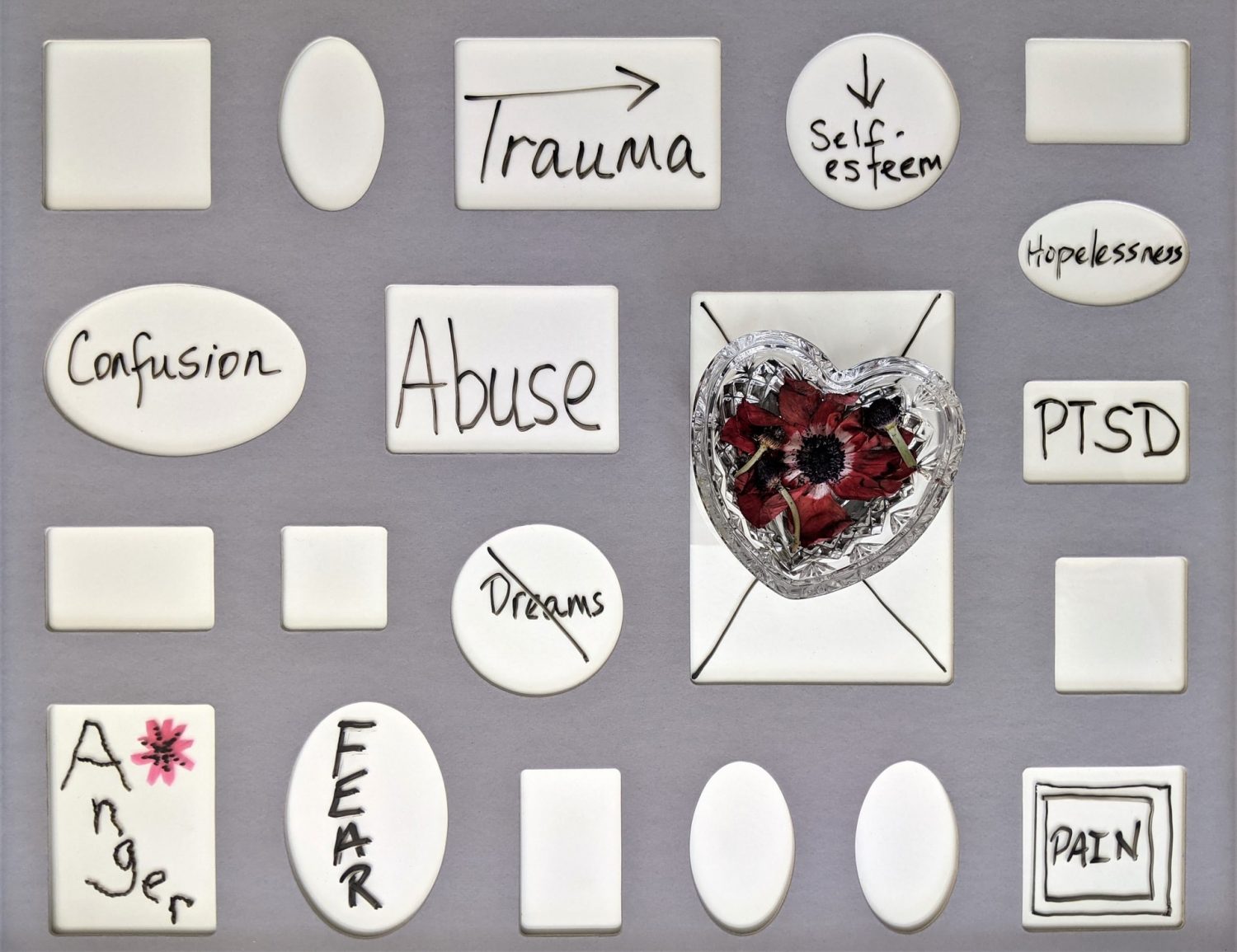

Photo by Susan Wilkinson on Unsplash

2 Comments

DoEs this apply to an abusive in -law?

How recent does the abuse have to be?

Isabelle, many thanks for your question. Ronagh has provided the following reply: Yes, abuse by an ‘in-law’ is covered, that is, abuse by the parent, grandparent, child, grandchild or sibling of the person’s spouse or civil partner. The relevant provisions came into operation on 21 February 2022, so abuse taking place since that date is covered.