2015 Westminster election: A small party’s dream or worst nightmare?

Smaller ‘third’ parties could play a pivotal role in this month's election, although Dr Christopher Raymond argues that the campaign exposes some serious limits to their long-term influence.

The upcoming 2015 Westminster election promises to feature small ‘third’ parties in a pivotal role. While UKIP, the Greens, the SNP, and the DUP, among others, could be the determining factor in the balance of power, this election campaign exposes some serious limits to the long-term influence of third parties.

Small in size but with big potential

First, the good news for small parties. If the opinion polls are to be believed (and they should be), this is going to be a good year for small parties. Despite their defeat at the polls in last year’s referendum campaign, the SNP are poised to dominate the upcoming election in the 59 Scottish seats, displacing dozens of Labour and Liberal Democrat incumbents in the process. In addition to their by-election wins this past autumn, UKIP are poised to play a major role in the outcome of the election, whether they win dozens of the seats in which the Conservatives and Labour are most vulnerable or just merely upset the balance of power in once-safe constituencies. The Greens are similarly to draw votes away from Labour and the Lib Dems. With this increased support, small parties are drawing increased media attention, requiring several (but not all) major third parties be included in the national television debate.

Beyond attracting attention and winning a few seats, many of these parties have the potential to determine who forms the next government. If the SNP dominate Scotland, a Labour government could be dependent upon their support (which could have ramifications for the future of the union). Because they threaten to steal seats away from both the Conservatives and Labour, UKIP could upset one or both parties’ chances of winning outright majorities. By drawing votes away from the Lib Dems and Labour, the Greens may spoil both parties’ chances of playing a role in the next government. The prospects of razor-thin majorities mean even parties from Northern Ireland (chief among them being the DUP) have kingmaker potential for propping up the Conservatives and Labour, respectively.

Potential downsides to success

Despite these exciting prospects for small parties, this election threatens to undermine the future relevance of third parties. Due to the UK’s first-past-the-post system, the Conservatives or Labour could win the 326 seats needed to form a single-party majority government on England’s 533 seats alone. (And if not by themselves, then both parties might be able to form a government with the Lib Dems, or at the very worst a Conservative-Labour coalition.) If UKIP and/or the Greens pose strong challenges in the heart of the two major parties’ main support, it would motivate an insular, England-centric focus by the two main parties to protect the lion’s share of the seats. This in turn might reduce the importance of third parties in the final outcome.

Diminishing importance

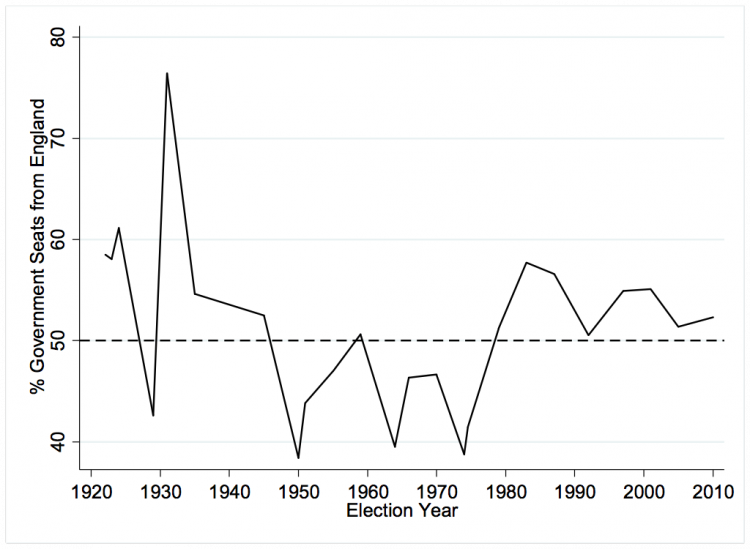

More troubling for small parties is Westminster parties’ diminishing dependence on support from voters in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. The SNP have been keen to highlight the lack of support in Scotland for the Conservatives, but it is true for Labour, too. This can be seen in the outcomes in English constituencies from 1922-2010. Specifically, when we look at the seat shares of governments won just in English constituencies (or governments that would have come to power anyway if they had been propped up by the Lib Dems, when the larger of these two parties do not control an outright majority in England), we see that Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland have been irrelevant to the outcome of elections since 1979. Prior to 1979, a few governments were able to win a majority of seats in Parliament just from the seats won in England, but most depended on seats elsewhere, too. Since 1979, governments could have come to power without any seats from Scotland, Wales, or Northern Ireland. This irrelevance dis-incentivises Westminster parties from focusing on voters outside England.

Even if nationalist parties seeking greater devolution were needed to support a government, success may come at the price of future relevance. While the SNP would enjoy more powers in exchange for propping up a Labour government, such a bargain would confirm that Labour (and the Conservatives) cannot count on seats in Scotland and thus should focus only on constituencies in England. Even if the DUP were needed to support a Conservative government, the two parties’ overlapping interests in reforming welfare would reduce Westminster’s financial commitments to Northern Ireland, and remove further Northern Ireland concerns from government policy. Further devolution to any region in exchange for government support might risk further alienating English voters seeking English self-rule, which in turn would mean even greater focus on placating English constituents.

Although the outcome of the 2015 election is difficult to predict, one thing is certain: the fate of small parties will play a major role. Whether they help shape the next government or spoil victory for one or both parties remains to be seen. However, the incentives facing the two major parties created by small-party success outside England might lead to more inward focus on English constituencies, potentially questioning the long-term viability of small parties.

Dr Christopher Raymond is a Lecturer in Politics at Queen’s University Belfast.

Parliamentary copyright images are reproduced with the permission of Parliament.